The stifling May heat slowly abates as the sun goes down. Behind the Qamishlo University in Northern Syria, a few people are at work in an empty lot transformed into a garden.

The air is fresher here than in town, less charged with dust and fumes from the poor-quality domestic oil fed into generators and motorized engines, stinking up the atmosphere and catching inthe throat. The volunteers at Keziyên kesk – the Green Braids – a group of young men and women, are busy pulling out the weeds around dozens of young tree seedlings, lined up in tight rows, before watering them carefully so as not to drown them.

The Kesiyên Kesk project started in October 2020. “Regional policies have damaged our environment and our ecological system. At least five rivers in Rojava now run dry. The regime never bothered about ecology. It wanted to turn the region into a wheat supply with no consideration for the inhabitants,” Ziwar Shewo explains as one of the spokespersons and co-founder of the project, and journalist on Ronahi. “Twenty five years ago, there were rivers, a greater variety of plants. Now the Autonomous Administration is in charge, we have the opportunity of repairing our environment. We must accept the fact it is in poor condition and that we must change this state of affairs. There are only 1.5% of green spaces in Rojava, while international recommendations are for 10 to 12% of the space to be thus occupied. The lack of a green cover means we suffer from the heat, the pollution and illnesses, that much more. In Syria, 80% of the cancer patients come from the North/Northeast. After we heard that ,we decided we had to do something as members of the civilian society. Since the Autonomous Administration and local authorities couldn’t handle it because of lack of funds, we decided to take on the project. We want all of our society to join in, by spreading the culture of tree plantings, something people don’t care about at the moment.”

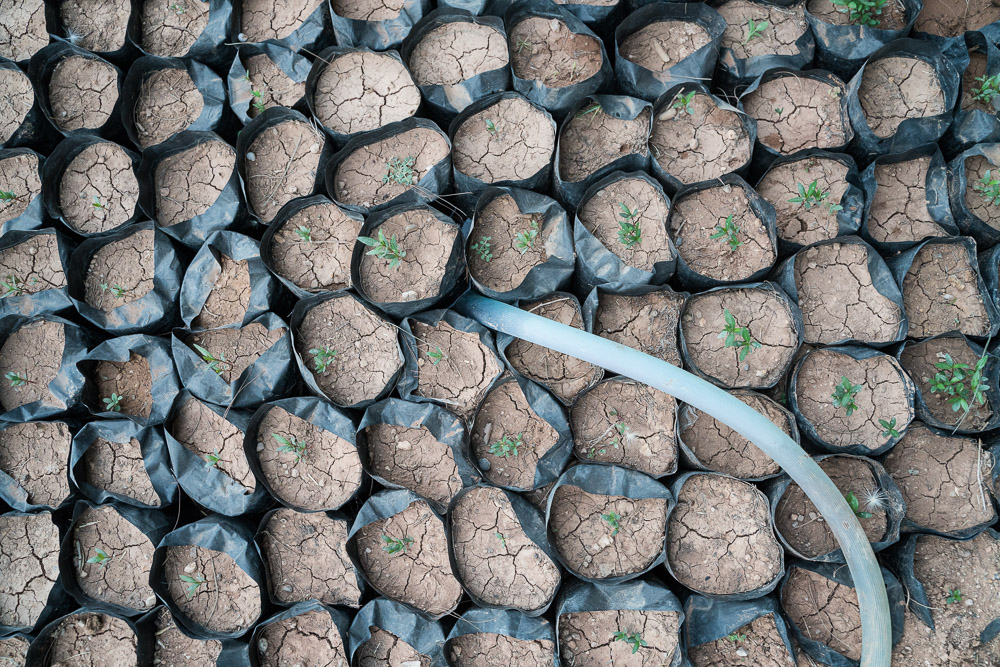

The volunteers aim at planting 4 million trees in the region. This would have cost 30 billion Syrian lira for seeds, – approximately one million dollars at the current exchange rate – an absolutely outlandish amount. For this reason, they called upon donations. The seeds were sent from all the towns in the zones under the control of the North and East Administration in Syria. “This has placed a great responsibility on us,” explains Sidar, a medical student. “We treat these plants like we would our own children.” Rojava University lent the land that now bears 80,000 seedlings – 95% of the seeds have sprouted: vines, fig trees, mulberries, pomegranates, now awaiting further growth before being planted somewhere in the Cizrê region. An abandoned empty lot has also been offered by the town, the volunteers have cleaned it up and are ready to start planting trees there. A scientific committee that includes agronomists shoulders the volunteers in order to examine the region for the best locations to plant these trees. For instance, along roadways, around villages with fruits trees, in schoolyards…

Initially founded by three friends and supported by a solid group of fifteen or so people from different fields, although intellectuals, students, journalists, civil servants and writers predominate, the project is open to all volunteers. Invitations were sent via social networks and met with great success, with dozens of people showing up for specific actions. Schools came to lend a hand, as well as the Federation of the war wounded. The project is independent of the Autonomous Administration and rooted in civilian society, willing to accept aid from any volunteer or structure.

The name Keziyên Kesk was chosen as a tribute to the struggle of women in Rojava, particularly Yezidi women whose husbands were killed by ISIS and who cut off their braids to tie them to their tombs, as a symbol of resistance.

Nazdar is 25 years old, she is a civil engineer and has been working several years for an NGO. “Jin comes from jiyan which comes from nature. Nature gives life, just as women do. If a woman likes to plant growing things, she will transmit this passion to her children, more than a man will. By changing the situation for women, you also change it for the future generation”, she says. “Our project is on a 5 year plan. We are only beginning. I heard about it through social networks and this is how I came here. I was looking to involve myself in this kind o f project, so I didn’t hesitate. At first, I worried it would only be about planting trees without caring any further about them. But things are planned for the long term here. The topic is of interest to the young ones, they even wrote a song for us. It is also a place where you can spend some time with like-minded people. We have very few such places. It allows for an exchange of ideas. Had the project been tied to a political organization, I would not have joined up. This is a project of the civilian society.”

Keziyên kesk has started to spead beyond Qamishlo, to Heseke and Darbasiyeh where committees are being organized. Other similar projects also exist in the region, notably the one at the Internationalist Commune, Make Rojava Green Again.

Another co-founder of the project, Mehmûd Çaqmaqî, is a writer orginally from Efrîn, a region invaded by the Turkish State and its back-up troops at the end of 2018. They forced a massive exodus of inhabitants, committed assassinations, rapes and robberies against those who remained as attested by the testimony of survivors. The occupying forces notably targeted the olive trees for which the region is famous. Shovel in hand, Mehmûd explains: “In Efrîn, they cut down the trees, close to 1,400 of them and kill the earth. Here, we are planting. We have no borders, we are ready to plant trees everywhere, including in Sere Kaniye and in Efrîn. We hope our activity will inspire people and encourage them to stay here instead of emigrating.”

To follow the activities of Keziyên kesk:

Facebook | Twitter @tress_green