The American Libertarian Socialist and Ecologist Murray Bookchin defined the ideal economy as a municipally led moral economy that is under democratic control. He argued that the communes’ control over the economy represents the highest developed form of Confederalism. These same principles are being applied in the economy in Rojava, the mainly Kurdish populated North of the Syrian state territory. This region was liberated in 2012 with the Revolution of Rojava, which came up with the popular uprisings in Syria and the greater region.

The political philosopher and imprisoned chairperson of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), Abdullah Öcalan, has linked Bookchin’s theories of social ecology to the historical development of communal life in the long history of the Middle East. The idea of the political concept formulated as “Democratic Confederalism” is to empower emancipatory forces within society that exist in rural structures and have not been commodified by capitalism and state society.

The model, under development in Rojava and highly inspired by the conclusions of Öcalan, is directly linked to the tradition of the last 10,000 years of history. It rejects statehood and stands for the self-government of societies and empowerment of communities, especially women, through all levels of society. This includes a democratisation not only of the political, but also of the social and economic spheres. The aimed for economy has been termed “democratic and communal economy”. This concept was developed from Democratic Confederalism’s form of socialism, as distinguished from both neoliberalism and state/real socialism. “Historically, the economy developed separately from society,” observed Dr. Dara Kurdaxi, a member of the economics commission in Afrîn. “That led to the establishment of exploitative states and, finally, economic liberalism. In contrast, state socialism, which diverged from its own economic ideas, made the economy part of the state and turned everything over to the state. But [state capitalism] is clearly not so different from multinational firms, trusts, and corporations… Historical experience has shown that we in Rojava must follow a different model.” Production should not be controlled by the state, nor by the private market, but through the communes and people’s councils, which are self-governing institutions, in a position to know the needs of their participants.

The Kurdish economic analyst Azize Aslan from North Kurdistan states the following: “Capitalism foregrounds exchange value, the production of things for the market. It rests entirely on the profit motive; production is not for the society, but for the market. But a society that cannot determine its economic activities is helpless even to improve the lot of its own workforce. We are forced to work for pathetic wages, for minuscule compensation, but we do it anyway. We work in the informal sector without job security, without unionisation, but we work regardless… An economic self-government is crucial for Democratic Autonomy; indeed, it is the precondition for Democratic Autonomy. A region that can’t decide on its own economy cannot be autonomous.”1

Rojava’s economic “underdevelopment” is simultaneously a great disadvantage and an opportunity. It allows the traditional social collectivism of the Kurdish people to be channelled positively to build a new, alternative economy. Indeed, integrating traditional structures is a typical approach of the Kurdish freedom movement, connecting tradition and emancipation. Also it needs to be stated that while on the one hand the embargo by all neighbours leads to a serious lack of many goods, on the other hand it supports the development of a self-sufficient economy based on solidarity and democracy.

In this sense with the liberation the Movement for a Democratic Society (TEV-DEM; in 2011 it initiated the direct democratic structures in Rojava and organised the liberation with the defence forces) discussed together with other sub-social movements like Kongreya Star (the women’s movement in Rojava), municipalities or the youth movement how a solidarity economy could be developed, and in this framework how initial co-operatives could be set up. Within TEV-DEM the founded committee for economy was mainly co-ordinating this policy, but also the communes at the base of the society have been involved directly. The strategy was to take the steps carefully and not be overhasty, which could lead to failures like in other social revolutions of humanity. So, in 2013 the first significant number of co-operatives were established, in the cities as well in the rural areas. The number increased in 2014 to some dozen, particularly on the state operated land which has been taken under control by TEV-DEM.

The establishment of co-operatives was one of the many discussions and strategic goals between 2012 and 2014 in Rojava. Communes and women’s structures were the ones within the revolutionary movement who led these discussions. However, at that time in the economy public companies controlled by TEV-DEM and private small companies were much more dominant. When the terror organisation Islamic States (IS/ISIS) attacked Kobanî in September 2014, for all Rojava a period of an intensive defence lasted until summer 2015. When a certain stability was achieved, the whole of society turned its attention to the economy more than ever. The need for economic structures which make Rojava economically more social-equal and independent from capitalists and capitalism, both within and outside of Syria, has been expressed stronger.

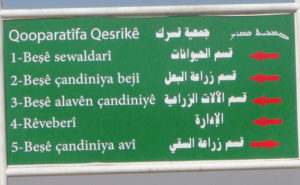

The economic sector has been reorganised anew in a more democratic way. For each canton an “assembly on economy” has been developed which consists of five sub-sectors: Industry, Trade, Agriculture, Co-operatives and Women’s Economy. Additionally, the committee of the Democratic Self-Administration, established in 2014, joins this assembly. It meets monthly and elects an economics committee as the executive body. The last two sectors of the five are the ones which apply the most pressure for an economy which gives spaces to everybody, limits exploitation, impedes lobbying and corruption and uses the existing sources in the interest of the whole of society. This form of organisation is an expression of the political approach – the society is diverse, but together comprises a whole. Not excluding, but rather incorporating, the capitalist elements of the economy, and then transforming them into something more solidary is the approach. This is one of the results learned from real socialism.

After two years of experience with co-operatives, a broad discussion for a contract on co-operatives started in 2015. Until 2015, the practices of the founded co-operatives were quite different and partly problematic. The pressure by traders with relationship to the Baath regime, PDK of Barzani in South Kurdistan, IS and even Turkey in connection with the embargo, has not limited the influence of capitalist structures on Rojava. These influences increased the profits of some traders, and even some big newly established co-operatives, in a negative way. Driven by the lack of some important basic goods and financial shortages and an adequate self-organisation structure of the economy sector, co-operatives like Hevgirtin or Kasrek developed like a company with many small and equal shareholders, rather than as a co-operative with the aim of solidarity and in the interest of the general society. These big “co-operatives” were established by the initiative of the economics committee against the growing power of private traders in 2015. They were partly successful and in some sectors could break the monopoly of the private traders, but they started to act partly in the same mentality as their competitors. However, after one year and broad discussion – in fall 2016 – the draft for a Co-operative Contract was approved, with many amendments by almost all political structures in Rojava and Northern Syria (meanwhile the liberated territories had grown quickly). Since then, the co-operative sector has had a much clearer framework, agenda and goals. This opened the way for the establishment of much more “real” co-operatives in Rojava.

Among other things, each new co-operative means more production in quantity and diversity. Considering that Northern Syria has produced only a part of the needs of society, this is a very crucial aspect. This is related to the capitalist centralisation of the economy by the Baath regime since the 70’s. While the many small private companies are only interested in fields which bring profit, co-operatives also have a social agenda. Co-operatives could be initiated in economic sectors where imports dominate.

Most agricultural co-operatives in Rojava are set up on land which was operated by the Syrian state. This is around 5% of all agricultural land. At the end of 2016, the economics committees decided to give this “public” land to people who form a co-operative and produce based on the Co-operative Contract. The existing communes around each piece of such socialised or communalised land came together and selected the people who should run it. Thus the established co-operative is responsible to the neighbouring communes. Here we see how the economy is connected to direct democratic structures. It is essential for a co-operative in Rojava that all co-operative members work for the co-operative and make decisions in a direct democratic way. The co-operative members need almost no money to start production because the economics committee lend the necessary tools and machines and give the seeds.

These co-operatives work the land, produce, primarily work for their own needs and secondarily the surplus production is being sold in local markets to the economics committee, or in some cases to private traders. The harvest in 2016 and 2017 was quite successful, and since then interest in co-operatives has grown significantly among the broader population.

According to the Co-operative Contract, 25% of the income must be reinvested in the co-operative’s activities, 20% is a kind of tax to the economics committee, and 5% needs to be forwarded to the “House of Co-operatives” (Kurdish: Mala Kooperatifen) which is a coalition of all co-operatives in the related district (usually consisting of one city and surrounding territory). They were set up in all districts of the three cantons of Rojava, and many other districts of the “Democratic Federation of Northern Syria” within 2017. This upper structure supports the co-operatives in its region in different ways, like consultation, in cases of urgency, and creates connections among the co-operatives. The House of Co-operatives consists of the co-chairs of all co-operatives, a woman and a man usually, and may even initiate co-operatives in production sectors where are no co-operatives.

The Houses of Co-operatives form the “Unions of Co-operatives” at canton level, which also concentrate on consultation, setting up new types of co-operatives, and the long-term political perspective of all co-operatives. In 2017, there were a lot of discussions about setting up co-operatives in the fields of energy, different forms of technology, or food control, for example. The aim is to have co-operatives in all economic sectors. Step by step, co-operatives should be present everywhere in order to have a strong influence on the economy. For this goal it is necessary to do comprehensive research. As the Syrian state did not leave any data on the economy, this is especially important.

Apart from agricultural co-operatives on communalised land, in a slower process, more and more small farmers are forming land co-operatives. When this happens it usually covers one village. The system is also based on the Co-operative Contract.

The number of co-operatives in cities is growing slowly. There are co-operatives for instance in the sectors of textile production, dairy products, sale of clothes, bakeries, cleaning, carpentry workshops, and translation. Either some communes come together to build up co-operatives, or the social movements do it. Here especially the women’s movement is active, that is why it is a separate and strong sector within the economics sector. Here they play a particularly progressive role.

The women’s co-operatives have spread to all regions of Northern Syria and are important in the comprehensive liberation of women. Until the revolution, only a small number of women had a job, although the education level was not bad in comparison to other countries in the Middle East. As women are active in each political and social field and area of Northern Syria, women are more and more involved in the economy. At end of 2017, a total of 6,000 women were members of co-operatives in the women’s movements, some thousand more in the others – also known as ‘mixed’ co-operatives. In general, the number of people involved in co-operatives was around 40,000, a number which should not be underestimated.

The Co-operative Contract states clearly that all co-operatives should work on ecological principles. The conservation of nature, the prevention of contamination of land, water and air and use of less chemicals for production are highly claimed principles which are implemented slowly, but constantly. For example, the use of local and organic seeds and fertilisers and the plantation of organic trees is spreading in the whole territory.

With the Co-operative Contract there is a clear line on what a co-operative and a private company are. The confusion can be overcome much more. There is still some confusion among a certain part of the population, because in the 80’s, the central government financially supported the establishment of co-operatives which were actually a company, people with shares who aimed to get as much profit as possible.

In October 2017 the first Conference of Co-operatives in Northern Syria was organised, with delegates from approximately 185 co-operatives. It was an important moment in the organisation of an economy of solidarity in the revolutionary process. The contribution of the co-operatives to the production, and specifically to the diversification of production, as well as to pushing back the capitalist mentality in Northern Syria, was emphasised. A crucial point was the decision to transform the existing “big co-operatives”, like Hevgirtin, into real co-operatives, and the transformation of public companies into co-operatives. Also strongly on the agenda was the creation of new co-operatives which distribute the products of all co-operatives to the society. The whole chain of production and distribution should be dominated by co-operatives. So far, each co-operative sells its products, which is sometimes very challenging.

In 2018, the numbers of co-operatives decreased by around 60. These were co-operatives which did not work so well, or were in conflict [all co-ops in Rojava must operate in line with the Co-operative Contract to be able to call themselves co-operatives]. Some of these were dissolved by the Houses of Co-operatives [which is elected as a co-ordination body of all co-ops in the district by the member co-ops]. But all other co-operatives work well, and in 2019 it is expected that the number will rise again. What is very important for the people involved in the co-operative is the quality and system of the work. They way of working in solidarity, producing, deciding, distributing, acting within the economy movement and society are important aspects. Also the accompanied discussion about the work of co-operatives is considered crucial. What is done should be done with conviction. The slogan of the Zapatistas “Lento, pero avanzo” [Slowly, but I go forwards] is implemented.

The long expressed goal of the co-operative economy is that 50% of economic activities will be covered by co-operatives; the remainder by mainly small scale private sector and public companies. As co-operatives are developed slowly so that the members are convinced of what they are doing, and not all people in the society are yet convinced by the solidarity economy, it is still too early to say how much to proceed with co-operatives in the economy. Consider also that the war and embargo against the revolution are ongoing, and a neo-liberal capitalist economy dominates the Middle East and world. Apart from that, there is no reliable experience worldwide where the majority of the economy is ruled by co-operatives.

How to understand the economy of Rojava

There are different opinions on how to characterise the existing economy in Rojava / Northern Syria. US-American activist David Graeber, who has visited Rojava twice, describes the economy of Rojava as being comprised of three layers: an international economy, connected to capitalist markets but prevented by the embargo; a market economy, regulated by the councils’ controlled prices, and a communal economy between the councils. Our experience agrees with this – it’s a mix of economies where everybody has a space. But it is an economy where the communal economy gets stronger step by step. The more political and ethical the society develops, the more the solidarity economy gets stronger.

In this way, the economic model of Rojava is being interpreted as a response to the neoliberalism of capitalist modernity, and a consequence of the critical discussion around state socialism. By building up a communal economy, the focus shifts from the exchange value to the use value of products. This shift of mentality has, according to Öcalan, the potential to solve the problems of unemployment that have defined the capitalist system. There are endless activities with high use values that can’t be quantified in terms of exchange and are, therefore, not seen as productive work.

In the continuous development of the solidarity economy of Rojava, which we were able witness during our research in the region, we see a big potential for building up a sustainable alternative to capitalist modernity. We are convinced that it is an important step for everybody seeking an end to exploitation and wage slavery. So it is necessary to stay informed and get in touch with the projects which are being build up in Rojava at the moment, and to defend the revolution of Rojava against the attacks by statism, feudalism, capitalism and patriarchy.

1 Azize Aslan, speech to the DTK’s “Democratic Economy” conference, Amed, reported in “Hedef Komünal bir Ekonomi,” Özgur Gündem, July 14, 2014, http://bit.ly/1DA8Ewu. See also Ayboga, Flach, Knapp 2015