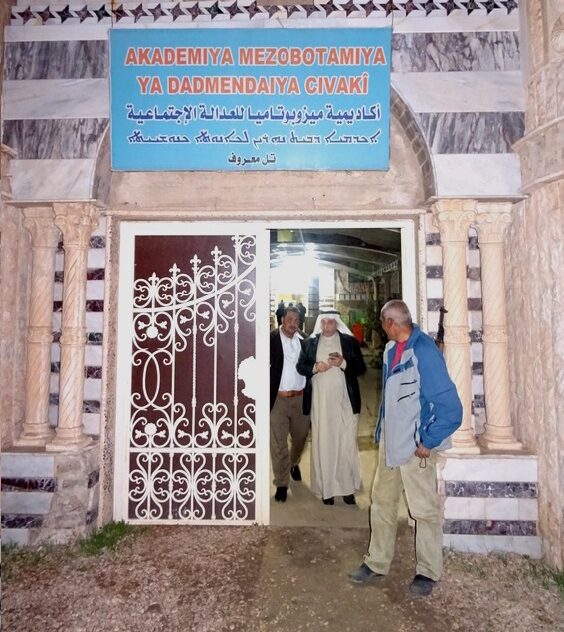

The Syrian regime under the Ba’ath Party of Bashar al-Assad is not only infamous for its war crimes and human rights abuses during the war in Syria, but also held a thick record of systematic violence prior to the uprisings in 2011. Apart from its extensive intelligence apparatus, its law and justice system enshrined authoritarianism and state power in the legal realm. The population of Syria, and minorities in particular, were taught to fear the law as the representative will of the oppressive state. In northern Syria, since the beginning of the revolution in Rojava in 2012, manifold initiatives have been systematically launched to undo the state and its domination not only in the realm of politics and society, but also in the psychology of people, who experienced not only Assad’s regime, but more recently the fascist rule of ISIS. Efforts are led not only in the sphere of law and justice, but also in the realm of grassroots-organizing, education and political, economic and social action. There are many difficulties however. What could an alternative, non-statist justice system look like? Let us take a look at Anja Hoffmann’s observations from an Arabic language justice academy in Tel Marouf…

Tel Marouf is a small town in northern Syria that was severely assaulted in 2014 by the extremist al-Nusra Front, the former Syrian branch of al-Qaeda that renamed itself as Jabhat Fatah al-Sham. The People’s Protection Units (YPG) and Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) resisted and eventually retook the area, but at the time, the entire population of Tel Marouf was forced to flee. Only recently, 340 out of the 600 households returned. Most of the infrastructure was damaged; even the local mosque had been bombed by the attackers.

On the edge of the town is a palace-like Arabic language academy of justice and law. At the time of writing, autumn 2018, the fourth educational cycle of the academy enabled 50 students, including 14 women to learn about the new justice system of the Democratic Self-Administration. Most of them are from Manbij, Raqqa or Deir ez-Zor and had been involved in the sphere of law and justice before the revolution. One participant, who was forced to live under ISIS occupation for five years, claimed that her experience led her to greatly value the notion of justice. The education included subjects like history and philosophy, the women’s question in the Middle East, and the justice system of the Democratic Self-Administration. The daily routine begins with physical activities at 6.30AM. After breakfast, classes start at 8AM and lasts until 7PM with several breaks in between, followed by one hour of self-education and preparation. The education lasts 45 days and follows a strict program.

In all regions of Northern Syria, justice commissions were formed to regulate legal disputes. Only if these were unable to solve any given problem at hand, the case would be taken to the Diwana Adalet (Board of Justice). As explained by one of the students, rather than merely coming to a judgement, the main aim was to find a solution that both parties could adequately live with. At the end of the education, a discussion took place to speak about the differences between the new system and the regime’s notion of law and justice.

Women’s Rights

Not only the women, but also the male participants of the education stressed great transformations in terms of the rights of women. Issues that primarily concern women are first addressed in the Mala Jin, the “women’s houses” that exist everywhere across the region. Most of the problems raised by women seem to be resolved at this first level. One participant described how in the past, the testimony of one man in court was equal to that of two female witnesses. Children were automatically put under the custody of the father after divorce, but now it was the other way around. Parallel to this, child marriage and polygamy were systematically fought in an ongoing struggle. The legal age for marriage was set at 18. After years of ISIS terror, women had disappeared from the public sphere. The new justice system however instituted their rightful place in society. During the regime era, the justice system was built on breaking women’s will, which was only further deepened by ISIS. Now however, law was to be on the side of women in such matters. In general, the new system does not make discrimination between different ethnic or religious backgrounds, age or gender. Women and men were to be equally represented in all spheres of life. The women at the academy said that they would like to see this legal system develop in all of Syria.

The society is solving its own problems

The main difference between the old and the new justice system is the fact that now it is the society, not the state that is solving people’s problems. In the past, it could take up to three to four years for legal disputes to be resolved, whereas now issues were settled within weeks, evoking much appreciation by the local populations. In the old system, the law was written and practiced in the interest of the rulers and was therefore untouchable. Judges and prosecutors were installed from above and were usually not from the local area. The task of justice and law was to punish – the purpose was motivated by revenge, not by a quest to find just solutions. The regime’s system had not changed since the 1970s, but with the revolution, things were to be radically transformed and changed.

Now each town district and village has peace and consensus committees that are generally accepted within society. The priority is not to impose solutions on society but to encourage these initiatives to develop within communities themselves. If no solution is achieved at this level, the case is taken to the Dadgeha Gel (People’s Court), which is formed by members of the town district committees.

The participants emphasize that the state had historically created conflicts and contradictions among the communities by treating them differently along state interests. This, as they explain, is a principle that ISIS employed as well. Now, they no longer see the need for a dominating power hierarchy, since justice is now accountable to all colors of society. Rather, they claim that ethics and morality constitute the foundation of their understanding of justice. After all, as they say, the different societies in the Middle East, despite their individual features and practices, do not differ radically from each other culturally.

The aim of the new justice system is to find a solution that satisfies all sides concerned, based on justice and mutual understanding. Now, as the members state, all colors of life are to be expressed. Their vision is a federal, free Syria based on democracy and solidarity of all peoples, in which people can come up with creative solutions to overcome their grievances.