Part 1: Socio-economic destruction

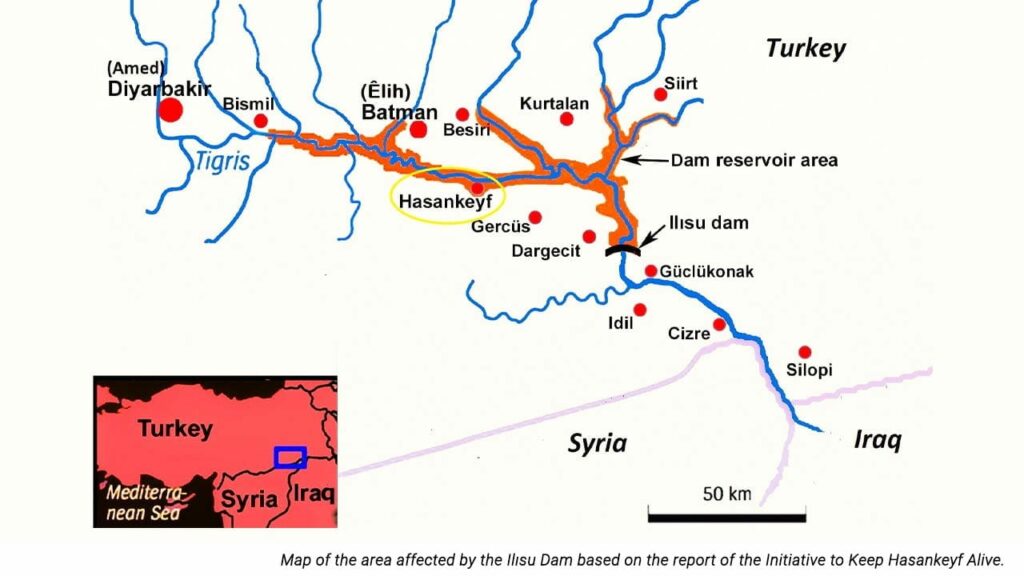

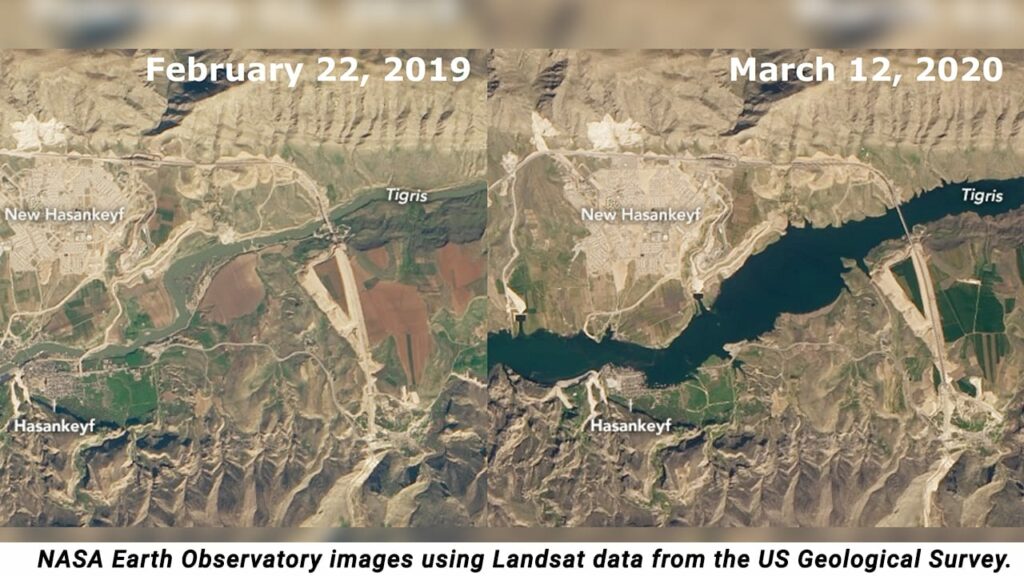

Hasankeyf, an ancient town in Turkey’s south-eastern province of Batman (Êlih) – with a history of 12,000 years of human settlement – was engulfed in 2019 by the reservoir of a controversial hydroelectric dam project.

Celebrated by the Turkish government as Turkey’s fourth largest dam, Ilısu dam on the River Tigris began to operate in July 2019, amid disputes between the Turkish government and several local and international environmental activists who have been campaigning against the dam project for years. The fear of destruction of the unique archaeological artefacts of Hasankeyf, the environmental concerns focusing on the preservation of the natural life on the Tigris Valley as well as the danger of displacement faced by thousands of valley inhabitants have been the key concerns of the struggle against the megaproject.

Despite the protests and the legal battles, which even reached the European Court of Human Rights, the dam project – the first draft plans of which went back to 1954 – was not halted. It finally resulted in the flooding and drowning of 199 residential areas, including Hasankeyf, by July 2019 when the reservoir behind the dam was filled.

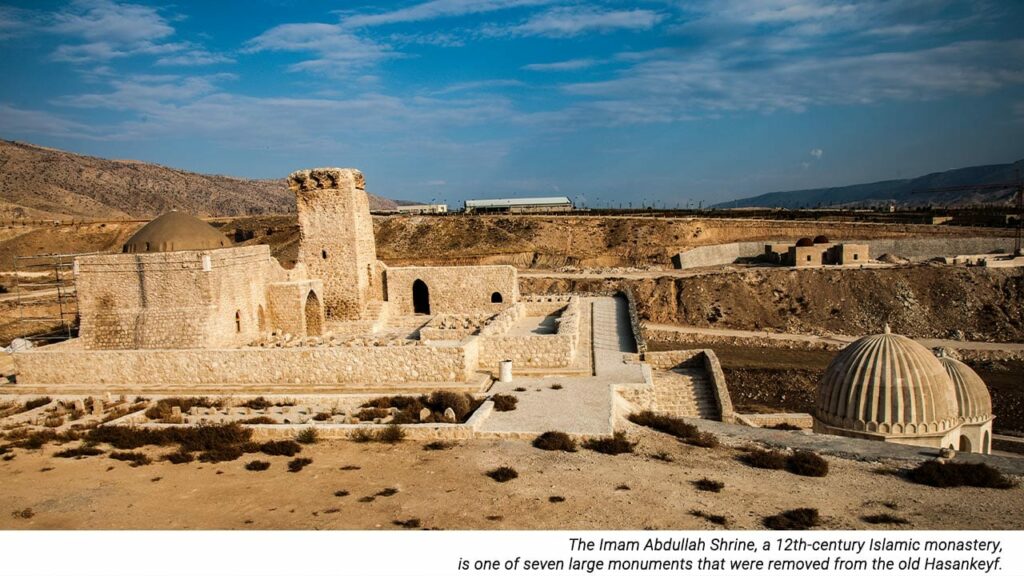

Whilst some pro-governmental mass-media organs celebrated the “relocation” of thousands of years old ancient artefacts alongside hundreds of old cemeteries, ironically enough, some touted the promotional boost that would be given towards “underwater” tourism in the region. Yet, it has not only been traces of the Silk Road or remains from the Roman Empire that have vanished, but also vast unexplored archaeological treasures which will irreversibly deteriorate underwater.

In this first of a two-part series, the residents and the shopkeepers of the “new” Hasankeyf spoke to MedyaNews about the socio-economic impacts of the megaproject on agriculture and tourism, the primary sectors sustaining the local economy.

Shopkeepers long for the ‘old’ Hasankeyf

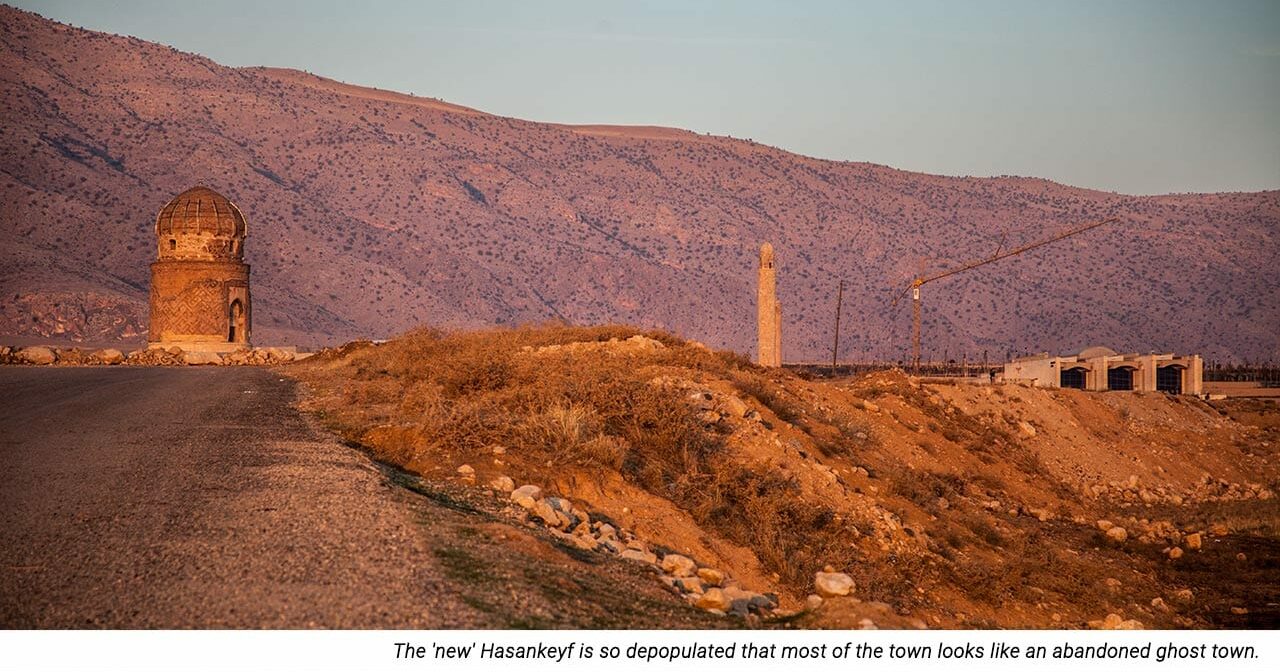

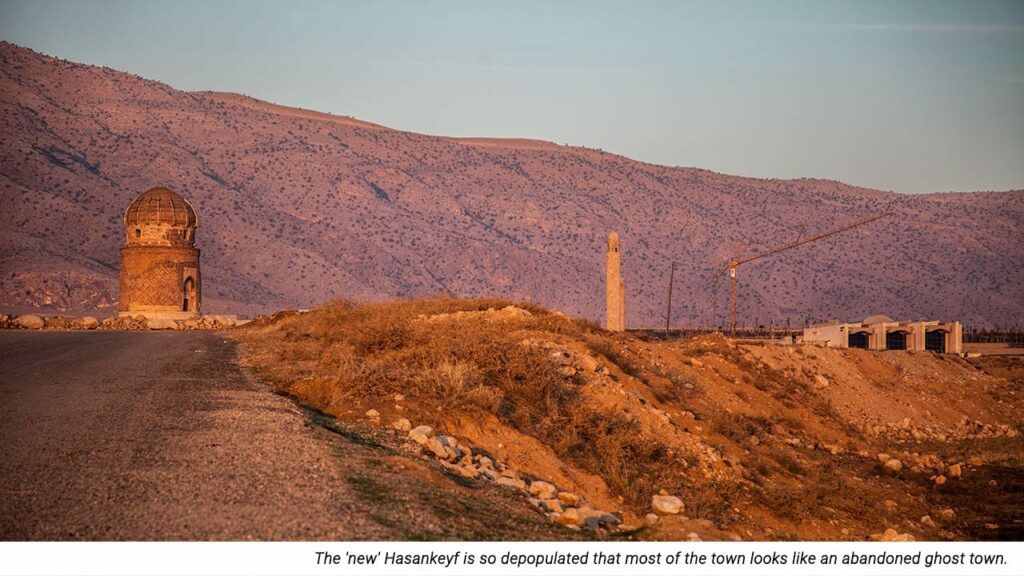

The main road reaching downtown Hasankeyf leads to a large hostel with a majestic Turkish flag welcoming visitors, but the road is so empty that it looks like a lost highway. Finally, reaching out to the path that goes down to the hills by the artificial lake, the huge empty valley feels deserted. The number of customers at the new Hasankeyf bazaar could be counted on the fingers of one hand. Above the hills of the new Hasankeyf, facing the lake that engulfed the old Hasankeyf, cafes and restaurants complete the image of an abandoned ghost town.

Sinan Bahçeci, a shopkeeper who runs a meatball buffet and who is a resident in the new Hasankeyf, reminisces about the old days when crowded tourist convoys would help to keep a lively cycle of trade between local shops: “When the tourists came, they used to come with tour buses in convoys. They would buy water from that kiosk, then come to my place to eat meatballs, then go to a café to drink their tea: it was like that. But now, we are stuck in the middle of nowhere”, he said. “Ask all the shopkeepers how the business is. Dull, they will say. There is no single tourist now”, he says.

The reason why the shops in Hasankeyf are about to be driven out of business is “the loss of our historical beauty”, Bahçeci said. “No one comes to Hasankeyf anymore. Would anyone come to watch the construction works? What is the sense of transporting historic pieces over here? They were beautiful in their old places”.

Bahçeci has lived all of his 44 years in Hasankeyf. He was born and raised in the caves which have now been engulfed by the reservoir’s waters. The state gave him a new house in the new Hasankeyf, but he has had to spend 50,000 TRY (Turkish Lira) to fix the problems in the “new” house. “My father died twice due to the dam project, can you imagine that?”, he said, highlighting the psychological distress that was caused alongside the financial difficulties he had to endure: “I had to move my father’s grave to the new Hasankeyf, otherwise he would have been engulfed like the rest of the old Hasankeyf”.

‘The average debt of a resident currently living here is around 150,000 TRY’

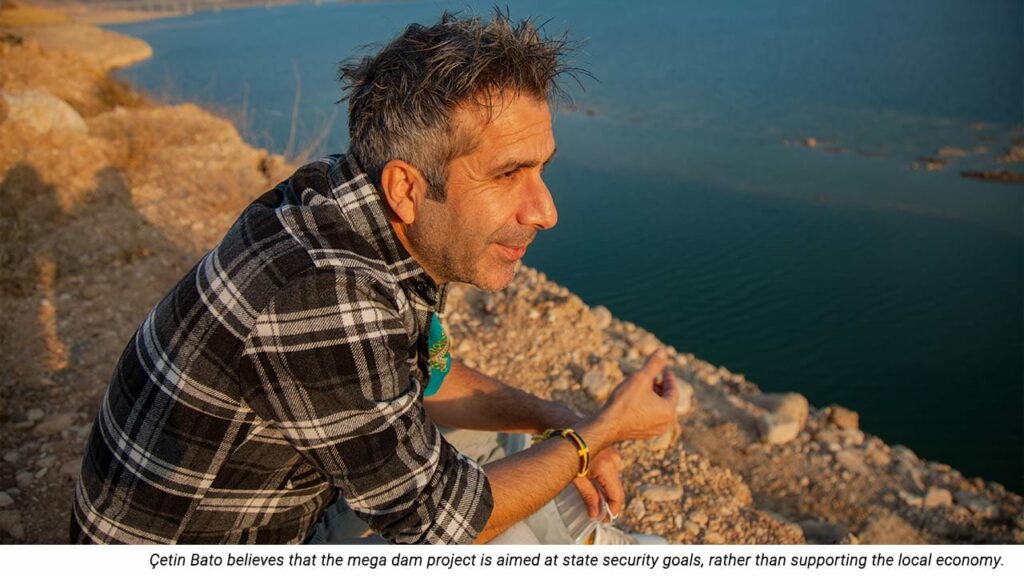

Çetin Bato is a resident currently living in the new Hasankeyf and the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) District Co-Chair of Hasankeyf. He states that the total amount of Tigris Valley inhabitants affected by this project is over 75,000. With such a massive population displaced, the “Ilısu Dam has social, economic and cultural impacts on Hasankeyf. People used to rely on agriculture as well as many other jobs which provided an income based on tourism in the area”, he says. “However, in the new Hasankeyf, the old and lively economic climate has disappeared. It is not a tourist attraction anymore, because the historical fabric of old Hasankeyf was destroyed”.

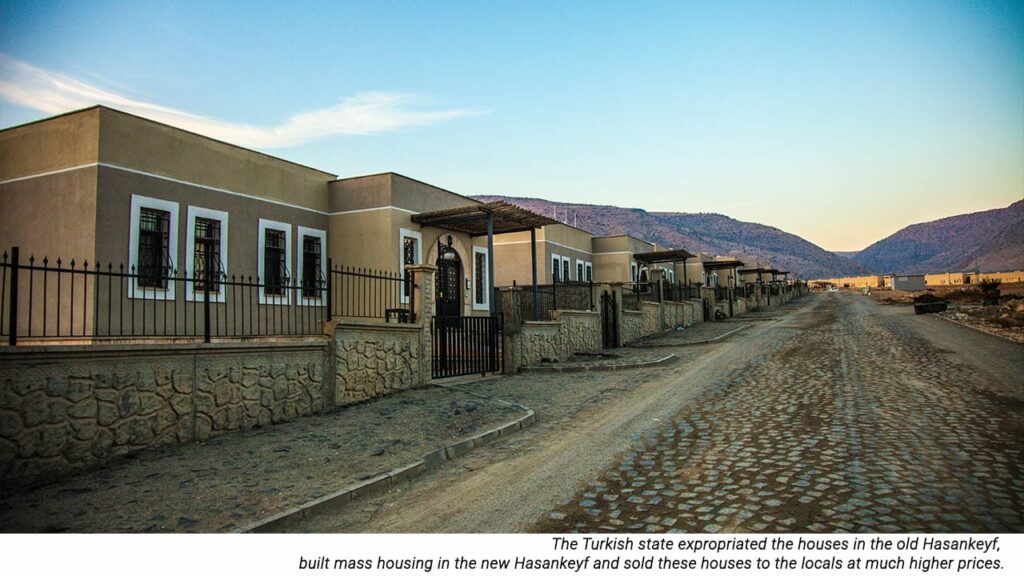

Bato stresses that the inhabitants of Hasankeyf are in debt due to the state’s handling of the megaproject. When the state expropriated their lands, the residents sold their homes to the state, but the new houses built on the new Hasankeyf were sold to them at higher prices. “The average debt of a resident currently living here is around 150,000 TRY (Turkish Lira). However, it is not just about the debts, but also the means to make a living. The state offered them no options for their old businesses that they lost”, he says.

The National Security Council proposed the dam project

Bato shares the concern that Ilısu dam was never about the energy policies or contributing to the local economy or providing water for agriculture. It was not the Ministry of Energy, but the National Security Council (MGK) who proposed this dam project. “When a decision is made by the military, then it is about security policies. There is an area inhabited by Kurds in the Kurdistan geography: how can we restrict the living space of the Kurds? How can we displace the people living here? This is the main question of this project”, he says.

“Did they open up an industry so that we can work? No. Did they develop an agriculture policy? No. Did they provide a trade circle? No”, the HDP’s Bato says. “The project never met the expectations of the locals. The state could not convince the residents of Hasankeyf about what they have done to Hasankeyf”.

No animal husbandry, no agriculture

Ali Ayhan was a shepherd for 20 years on the mountains of Hasankeyf. He had to quit his profession of herding goats and sheep when the owners of the animals had to migrate. “My life has changed after the dam. It is almost one and a half years, but I have not been able to pull myself together. We are hit economically and the problems have just begun”, he says.

Ayhan used to earn his living as a tourist guide when he came down from the mountains after weeks of herding, but “there is no tourism now. There is no agriculture and no animal husbandry. You cannot breed animals in the new Hasankeyf. You cannot even feed chickens”.

The shepherd adds that there is no joy in Hasankeyf now. “Our friends, our neighbours are gone. I was born and raised in these mountains, surrounded by history. I know the history and I know that the rose is beautiful uncut from its branch. I wish the ancient sites would be preserved in their own places. The mosque, the minaret, the castle gate … We long for our old days, our childhood, our dreams”, he said.

‘When we criticize, they accuse us of terrorism’

Another shopkeeper agreed to voice his criticisms anonymously, due to security reasons. “The contractors, who are the partisans of the man who rules us (referring to President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan), renovate the same street again and again. They spin their wheels of money like that. We opened our shops last year. We have been desperate to earn income since then”, he said.

The 48-year-old business owner has been selling souvenirs and items in Hasankeyf for around 20 years, but only after 2019 when the old Hasankeyf was swallowed up, did his business face its worst crisis because his shop in the old Hasankeyf was engulfed by the reservoir waters as well. He complains that whenever they tried to raise critical voices about what was happening, they were accused of being either a member of the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) or FETÖ, the ‘Fethullahist Terrorist Organisation’ – as the Justice and Development Party (AKP) refers to the Gulenist Movement. “When we talk, they say: ‘Shut up. You are either from the PKK or FETÖ’. I speak up on behalf of no organization. I am the PKK of my bread, the FETÖ of my bread”.

‘People regret making the deal’

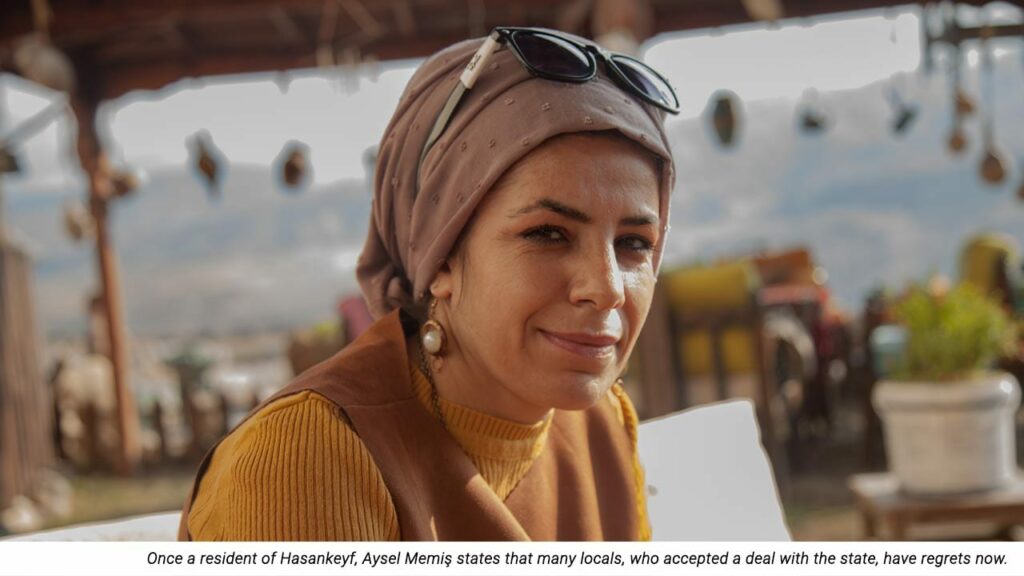

Aysel Memiş had been living in Hasankeyf, but now she is amongst the approximately 75,000 inhabitants who had to migrate after the dam began to operate. “We struggled against this, held marches, but could not succeed. They (the state) told us that we would give you this much of money in return for your former homes and they built these new buildings in the new Hasankeyf. Many locals accepted the deal, but later on everybody had regrets. Most people had to migrate. People regret making the deal, but it is too late now. They lost Hasankeyf”, she says.

Local tourism was hit hard when the history of Hasankeyf was submerged by the waters of the reservoir of this megaproject, observed Memiş. “They moved the history over here, so what? There is no sense to it anymore. Nothing catches my interest here anymore. Our history is buried under the water: the people of old times are gone, the cemeteries … This affected tourism the most”, she says. “Some people still come, just look around and then leave. What are they going to tell the visitors? Is there anything to show them? Nothing is left here but the mountains”.

Part 2: Bio-politics as an ‘ecological war tool’

Medya News continues with its series of interviews with people in Hasankeyf in the south-eastern province of Batman (Êlih) in Turkey. Hasankeyf, an ancient town, was engulfed in 2019 by the reservoir of a controversial hydroelectric dam project.

The filling of the reservoir of the dam not only caused 12,000 years of continuous human life in this ancient Mesopotamian town to be interrupted, but also deeply affected the biodiversity of the Tigris valley.

In this second part of the series, interviews were conducted with local activists who have been part of the campaign to protect Hasankeyf and the Tigris valley. They spoke to Medya News about the environmental impacts of the Ilısu dam and their ecological struggle to protect Hasankeyf and the Tigris valley from the impacts of the Ilısu dam – a massive hydroelectric dam, the first turbines of which were switched on by Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

Local residents have been displaced and endemic species and many bird species have ‘vanished’

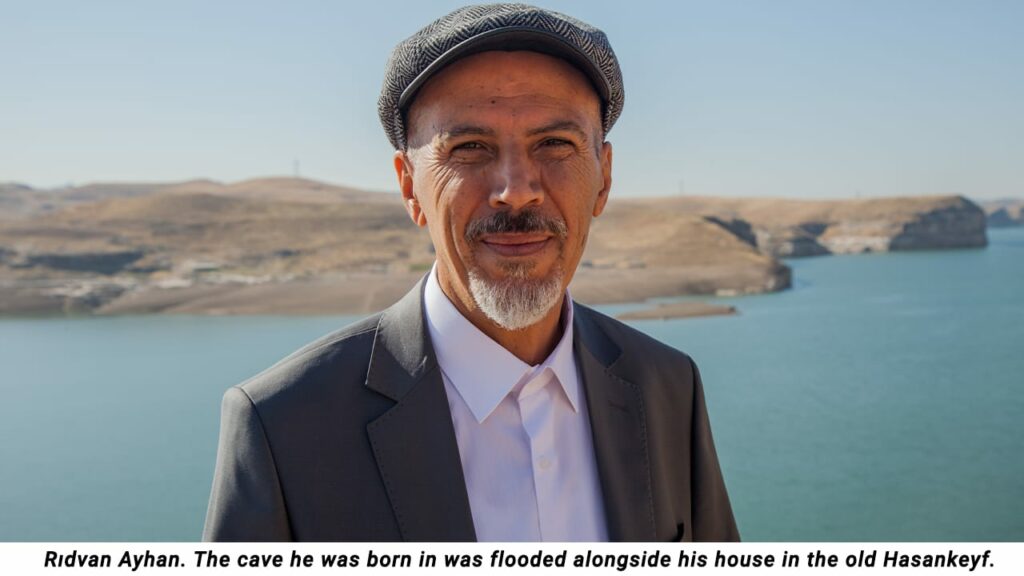

After the reservoir of the Ilısu Dam was filled, not only 85% of the historical artefacts and sites of Hasankeyf was destroyed, but “the ecosystem was terribly damaged. All the living creatures and the flora lost their habitats. The endemic species and many bird species vanished off the face of Hasankeyf. The level of moisture increased, had a negative impact on both the animals nested in Hasankeyf and the humans, especially the elderly. We cannot breathe healthily now”, said Rıdvan Ayhan, a devoted activist and the spokesperson of the Initiative to Keep Hasankeyf Alive, which was formed by locals and volunteers in 2006.

Looking down at the artificial lake from a vantage point at the top of a hill on the road to Hasankeyf, where the village ‘Shikefta’ (Şıkefta) – a residential area – vanished under water, Ayhan said: “In that place you see, under the water there, there were the caves and homes of the former residents. Due to the Ilısu Dam, the residents of these caves were displaced. They had their vineyards, orchards, gardens and animals, but they lost them all due to the Ilısu dam. No animal is able to live here now, because there is no pasture left to feed the animals. Therefore, all the villagers had to migrate”.

After years of struggle to protect Hasankeyf, Ayhan was sentenced to a prison term of over a year due to his struggle to halt the dam project. The cave he was born in was engulfed as well as his house in Hasankeyf. ‘What is next for Hasankeyf, is the struggle over?’, he was asked. His reply: “Never. The eco-system of Hasankeyf still needs protection and there is still a lot to do to save it. Our caves were our sweet homes and no apartment they build can be a home to me now. Our struggle shall and will continue until the reliction of the dam water is assured”.

As animals get sick, ‘we live in drought conditions, encircled by water’

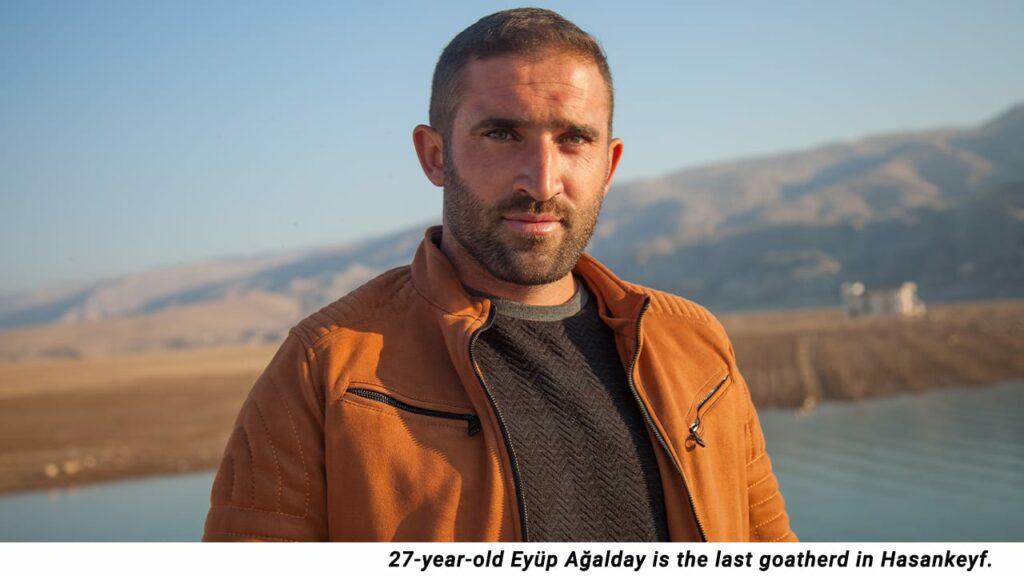

“It was all green at the waterfront of old Hasankeyf. We had small lakes and trees and bushes: all of these were natural resources to feed our animals. Whilst there were around 100,000 hectares (247,105 acres) of green-fields in the old Hasankeyf, they say there are 500,000 hectares of green-fields now, but there are none. They have only planted 14,000 trees, but these trees can only grow in a few years”, said Eyüp Ağalday, a 27-year-old who is now the last goatherd living in Hasankeyf.

Ağalday has been actively supporting the cause to protect Hasankeyf for years as he has been the direct witness of the environmental impacts of the dam. “We live in drought conditions, encircled by water”, he said, whilst describing the harm to the aquatic ecosystem that has been caused by the high tides and low tides of the dam, which the fish as well as the herds of Hasankeyf’s shepherds have suffered from.

“As Hasankeyf began to become more flooded under the rising waters of the dam, especially after the summer of 2020, our animals began to get sick. The animals are afraid to drink the waters of the dam. Since the water has flooded areas, many marshes have been created. The cattle of our neighbours have got trapped in the marshes. It has been so hard to take them to safety sometimes. The water of the dam is everywhere, but we do not even have fish. Fish die due to the tidal flows of the dam’s waters. The water will rise up and then go down, there will be marshes and droughts. We may sell our animals, because our animals are really in such a poor condition now”.

Most of the cultivated areas, the wheat fields and the cornfields are engulfed, Ağalday observes. “The gardens and the trees dried up. They said they would turn the fields into wetlands, but when the fields came out to the surface after they were engulfed, they all turned into marshlands. Only a few families are left now, who still do farming like us”.

‘Security’ dams used as ‘ecological war’ tools

Topographical engineer Agit Özdemir of the Union of Chambers of Turkish Engineers and Architects (TMMOB) stated that the total installed power of the Ilısu dam stands at 1,200 megawatts. “The total installed power of the Ilısu dam stands at 1,200 megawatts. Even when operated at full efficiency, the total production of energy is at 35% of its capacity. So, this dam cannot meet 1% of the country’s energy needs”.

Özdemir refers to the data of a field study that was conducted by the researchers of Dicle University to highlight how the Ilısu dam causes ecological destruction in the region. “The Tigris valley has been home to 266 endemic species. 66 of those 266 endemic species were living in the areas directly facing the impacts of the Ilısu Dam. 311 square km of the habitat of all living creatures were submerged. The state disregarded such field studies, which many researchers and civil activists were involved in to protect the Tigris valley. There was no Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) report when the Ilısu Dam project was first launched”, he said.

As an ecological activist in the the struggle to save the Tigris valley and Hasankeyf, he describes what he sees and experiences as a multi-layered struggle which is centred on an ecological struggle that has organised and enlarged itself into a collective struggle against the dam. “The ecology of the Tigris valley is not limited to the flora and fauna: all natural, biological, historical and cultural assets form the ecology of the valley. The state mobilises all bio-political power to interrupt all organic-natural-historical life in the region. Within this perspective, we have reasons to consider the Ilısu dam as an ‘ecological war tool’. Official documents of some state institutions address the Ilısu dam as a ‘security dam’. What we understand from their concept of ‘security’ is forcing the inhabitants of the villages to migrate, which had been burned down and depopulated during the 1990’s. Only this time, via ‘manufacturing consent’, a more refined and vague way to force people to leave is undertaken”.

Forced migration must be seen as part of the ecological question

Özdemir noted that the Ilısu dam engulfed not only Hasankeyf, but in total 199 rural settlements, all of which constitute an integral part of the ecology of the Tigris valley. “We should take into consideration the sociological and psychological connotations of the ecological destruction. Around 90 of these villages had faced forced displacement when they were burned down and evacuated in the 1990’s. The hope of return has been destroyed for thousands of people who had been displaced and forced to migrate to the cities. When we take the concept of ecology, we cannot disregard this phenomenon, because we consider the social dimension of the environmental destruction within a dialectic that relates to the ecological question”, he said.

“After the activation of the Ilısu dam in July 2019, up to 100,000 people were forced to migrate, including around 3,000 nomadic families (known as “Koçers”, who are a special nomadic minority to be protected). They lost their natural living areas that are necessary to continue their subsistence economy – a unique economic model outside the system”, he noted. “They lived in a non-capitalist, non-industrial environment.

They terminated the organic life of these villagers who survived on agricultural production and lived in harmony with nature, planting their own vegetables in their own gardens and farms. These villagers were forced to migrate to the big cities to be the prospective cheap work force”.

The struggle in Hasankeyf should not be considered as a lost cause, according to TMMOB’s Özdemir. “The ecological activists in Kurdistan and around the world have gained an important experience in Hasankeyf. In Hasankeyf, what they actually wanted was to engulf the truth, to bury the truth underwater. So, our ecological struggle is a part of our quest for the truth, which will continue”, he said.