As the prospect of Kurdish independence becomes ever more imminent, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party transforms itself into a force for radical democracy.

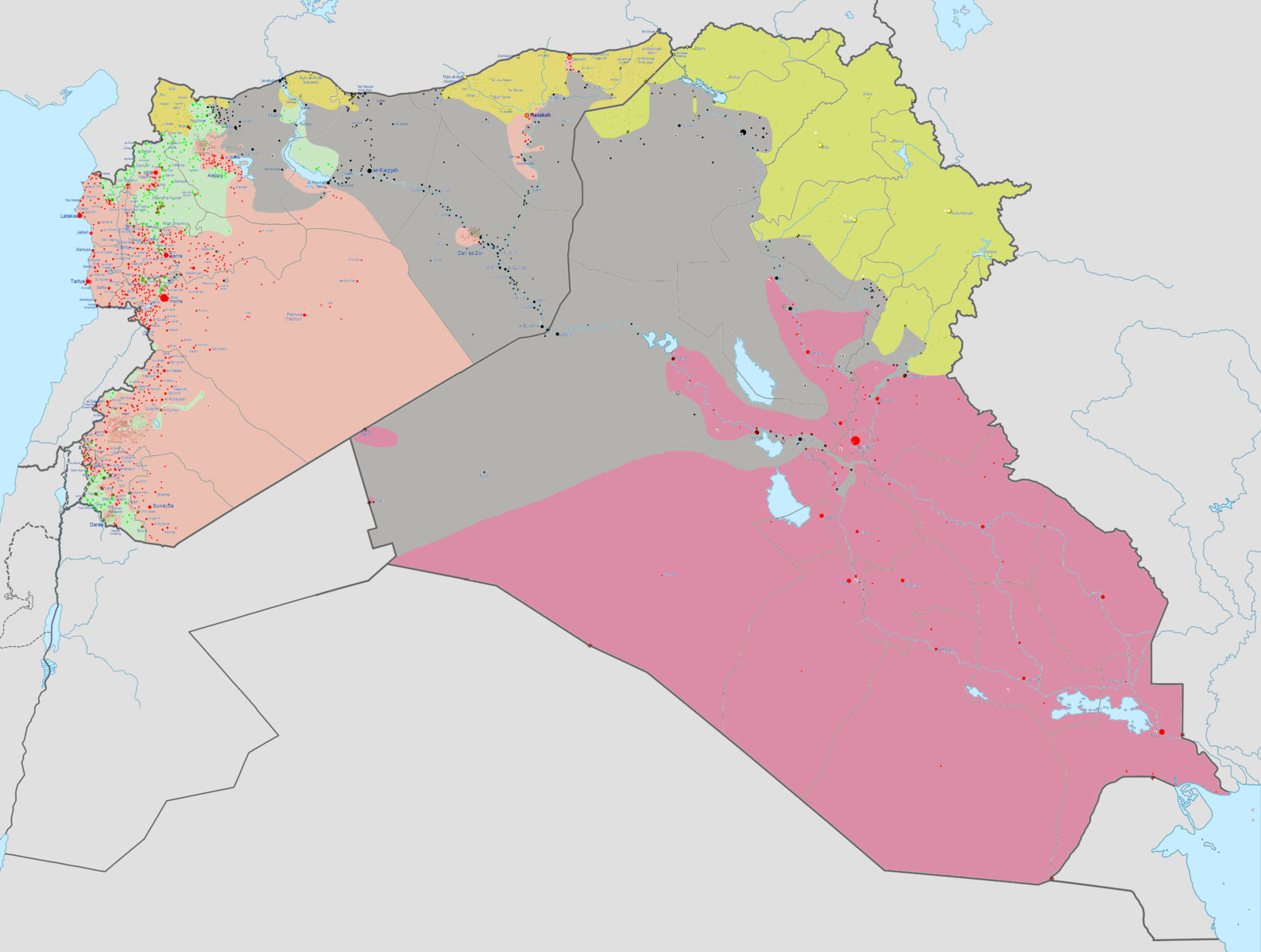

Excluded from negotiations and betrayed by the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne after having been promised a state of their own by the World War I allies during the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire, the Kurds are the largest stateless minority in the world. But today, apart from a stubborn Iran, increasingly few obstacles remain to de jure Kurdish independence in northern Iraq. Turkey and Israel have pledged support while Syria and Iraq’s hands are tied by the rapid advances of the Islamic State (formerly ISIS).

With the Kurdish flag flying high over all official buildings and the Peshmerga keeping the Islamists at the gate with the assistance of long overdue US military aid, southern Kurdistan (Iraq) join their comrades in western Kurdistan (Syria) as the second de facto autonomous region of the new Kurdistan. They have already started exporting their own oil and have re-taken oil-rich Kirkuk, they have their own secular, elected parliament and pluralistic society, they have taken their bid for statehoodhood to the UN, and there is nothing the Iraqi government could do — or the US would do without Israeli support — to stop it.

The Kurdish struggle, however, is anything but narrowly nationalistic. In the mountains above Erbil, in the ancient heartland of Kurdistan winding across the borders of Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria, a social revolution has been born.

The Theory of Democratic Confederalism

At the turn of the century, as the lifelong US radical Murray Bookchin gave up on trying to revitalize the contemporary anarchist movement under his philosophy of social ecology, PKK founder and leader Abdullah Öcalan was arrested in Kenya by Turkish authorities and sentenced to death for treason. In the years that followed, the elderly anarchist gained an unlikely devotee in the hardened militant, whose paramilitary organization — the Kurdistan Workers’ Party — is widely listed as a terrorist organization for waging a violent war of national liberation against Turkey.

In his years in solitary confinement, running the PKK behind bars as his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, Öcalan adopted a form of libertarian socialism so obscure that few anarchists have even heard of it: Bookchin’s libertarian municipalism. Öcalan further modified, rarefied and rebranded Bookchin’s vision as “democratic confederalism,” with the consequence that the Group of Communities in Kurdistan (Koma Civakên Kurdistan or KCK), the PKK’s territorial experiment in a free and directly democratic society, has largely been kept a secret from the vast majority of anarchists, let alone the general public.

Although Öcalan’s conversion was the turning point, a broader renaissance of libertarian leftist and independent literature was sweeping through the mountains and passing hands between the rank-and-file after the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. “[They] analysed books and articles by philosophers, feminists, (neo-)anarchists, libertarian communists, communalists, and social ecologists. That is how writers like Murray Bookchin [and others] came into their focus,” Kurdish activist Ercan Ayboga tells us.

Öcalan embarked, in his prison writings, on a thorough re-examination and self-criticism of the terrible violence, dogmatism, personality cult and authoritarianism he had fostered: “It has become clear that our theory, programme and praxis of the 1970s produced nothing but futile separatism and violence and, even worse, that the nationalism we should have opposed infested all of us. Even though we opposed it in principle and rhetoric, we nonetheless accepted it as inevitable.” Once the unquestioned leader, Öcalan now reasoned that “dogmatism is nurtured by abstract truths which become habitual ways of thinking. As soon as you put such general truths into words you feel like a high priest in the service of his god. That was the mistake I made.”

Öcalan, an atheist, was finally writing as a free-thinker, unshackled from Marxist-Leninist mythology. He indicated that he was seeking an “alternative to capitalism” and a “replacement for the collapsed model of … ‘really existing socialism’,” when he came across Bookchin. His theory of democratic confederalism developed out of a combination of inspiration from communalist intellectuals, “movements like the Zapatistas”, and other historical factors from the struggle in northern Kurdistan (Turkey). Öcalan proclaimed himself a student of Bookchin, and after a failed email correspondence with the elderly theorist, who was to his regret too sick for an exchange on his deathbed in 2004, the PKK celebrated him as “one of the greatest social scientists of the 20th century” on the occasion of Bookchin’s death two years later.

The Practice of Democratic Confederalism

The PKK itself has apparently taken after their leader, not only adopting Bookchin’s specific brand of eco-anarchism, but actively internalizing the new philosophy in its strategy and tactics. The movement abandoned its bloody war for Stalinist/Maoist revolution and the terror tactics that came with it, and began perusing a largely non-violent strategy aimed at greater regional autonomy.

After decades of fratricidal betrayal, failed ceasefires, arbitrary arrests and renewed hostilities, on April 25 of this year the PKK announced an immediate withdrawal of its forces from Turkey and their deployment to northern Iraq, effectively ending its 30-year-old conflict with the Turkish state. The Turkish government simultaneously undertook a process of constitutional and legal reform to enshrine human and cultural rights for the Kurdish minority within its borders. This came as the final component of long-awaited negotiations between Öcalan and Turkish Prime Minister Erdoğan as part of a peace process that began in 2012. There has been no PKK violence for a year and reasonable calls for the PKK to be delisted from the worlds’ terrorist lists are being made.

There remains, however, a dark history to the PKK — authoritarian practices which sit ill beside its new libertarian rhetoric. Raising money through the heroin trade, extortion, coercive conscription and general racketeering have been claimed or attributed to branches at various times. If true, no excuses can be made for this type of thuggish opportunism, despite the obvious irony that the genocidal Turkish state itself was in no-small part funded by a lucrative monopoly on the legal export of state-grown “medical” opiates to the West and made possible by its conscription and taxation for a massive counter-terrorism budget and oversized armed forces (Turkey has NATO’s second largest army after the US).

As is the customary hypocrisy of the war on terror, when national liberation movements mimic the brutality of the state, it is invariably the unrepresented who are branded as the terrorists. Öcalan himself describes this shameful period as one of “gangs within our organization and open banditry, [which] arranged needless, haphazard operations, sending young people to their death in droves.”

Anarchist Currents in the Struggle

As a further sign that it is abandoning its Marxist-Leninist ways, however, the PKK have recently begun to make explicit overtures to anarchist internationalism, even hosting a workshop at the International Anarchism Gathering in St. Imier, Switzerland in 2012, which lead to confusion, dismay and debate online, but which went largely unnoticed by the wider anarchist press.

Janet Biehl, Bookchin’s widow, is one of the few western anarchists to study the KCK on the ground, and has written extensively about her experiences on the New Compass website, also sharing interviews with Kurdish radicals involved in the day-to-day operations of the democratic assemblies and federal structures, as well as translating and publishing the first book-length anarchist study on the subject: Democratic Autonomy in North Kurdistan: The Council Movement, Gender Liberation, and Ecology (2013).

The only other English-speaking anarchist voice is the Kurdistan Anarchist Forum (KAF), a pacifist group of Iraqi Kurds living in Europe who claim not to “have any relationships with other leftist groups.” While supporting a federated Kurdistan, the KAF declares that it will “only support the PKK when they give up the armed struggle completely, engage in organising popular grassroots mass movements for the sake of achieving the people’s social demands, denounce and dismantle centralised and hierarchical modes of struggle and instead turn to federated autonomous local groups, end all relations and dealings with the states of the Middle East and the West, denounce charismatic power politics, and convert to anti-statism and anti-authoritarianism — only then will we be happy to cooperate with them fully.”

Following Bookchin to the Book

That day (minus the pacifism) might not be far off. The PKK/KCK appear to be following Bookchin’s social ecology to the book, with almost everything up to and including their contradictory participation in the state apparatus through elections, just as prescribed in the literature.

As Joost Jongerden and Ahmed Akkaya write, “Bookchin’s work differentiates between two ideas of politics, the Hellenic model and the Roman,” that is, direct and representative democracy. Bookchin sees his form of neo-anarchism as a practical revival of the ancient Athenian revolution. The “Athens model exists as a counter- and under-ground current, finding expression in the Paris Commune of 1871, the councils (soviets) in the spring-time of the revolution in Russia in 1917, and the Spanish Revolution in 1936.”

Bookchin’s communalism contains a five-step approach:

- Empowering existing municipalities through law in an attempt to localize decision-making power.

- Democratize those municipalities through grassroots assemblies.

- Unite municipalities “in regional networks and wider confederations … working to gradually replace nation-states with municipal confederations”, whilst insuring that “’higher’ levels of confederation have mainly coordinative and administrative functions.”

- “Unite progressive social movements” to strengthen civil society and establish “a common focal point for all citizens’ initiatives and movements”: the assemblies. This cooperation is “not [perused] because we expect to see always a harmonious consensus, but — on the contrary — because we believe in disagreement and deliberation. Society develops through debate and conflict.” In addition, the assemblies are to be secular, “fight[ing] against religious influences on politics and government,” and an “arena for class struggle.”

- In order to achieve their vision of a “classless society, based on collective political control over the socially important means of production,” the “municipalization of the economy,” and a “confederal allocation of resources to ensure balance between regions” is called for. In layman’s terms, this equates to a combination of worker self-management and participatory planning to meet social needs: classical anarchist economics.

As Eirik Eiglad, Bookchin’s former editor and KCK analyst, puts it:

Of particular importance is the need to combine the insights from progressive feminist and ecological movements together with new urban movements and citizens’ initiatives, as well as trade unions and local cooperatives and collectives … We believe that communalist ideas of an assembly-based democracy will contribute to making this progressive exchange of ideas possible on a more permanent basis, and with more direct political consequences. Still, communalism is not just a tactical way of uniting these radical movements. Our call for a municipal democracy is an attempt to bring reason and ethics to the forefront of public discussions.

For Öcalan, democratic confederalism means a “democratic, ecological, gender-liberated society,” or simply “democracy without the state.” He explicitly contrasts “capitalist modernity” with “democratic modernity,” wherein the formers’ “three basic elements: capitalism, the nation-state, and industrialism” are replaced with a “democratic nation, communal economy, and ecological industry.” This entails “three projects: one for the democratic republic, one for democratic-confederalism and one for democratic autonomy.”

The concept of the “democratic republic” essentially refers to attaining long denied citizenship and civil rights for Kurds, including the ability to speak and teach their own language freely. Democratic autonomy and democratic confederalism both refer to the “autonomous capacities of people, a more direct, less representative form of political structure.”

Meanwhile, Jongerden and Akkaya note that “the free municipalism model aims to realize a bottom-up, participative administrative body, from local to provincial levels.” The “concept of the free citizen (ozgur yarttas) [is] its starting point,” which “includes basic civil liberties, such as the freedom of speech and organization.” The core unit of the model is the neighborhood assembly or the “councils,” as they are referred to interchangeably.

There is popular participation in the councils, including from non-Kurdish people, and whilst neighbourhood assemblies are strong in various provinces, “in Diyarbakir, the largest city in Turkish Kurdistan, there are assemblies almost everywhere.” Elsewhere, “in the provinces of Hakkari and Sirnak … there are two parallel authorities [the KCK and the state], of which the democratic confederal structure is more powerful in practice.” The KCK in Turkey “is organized at the levels of the village (köy), urban neighbourhood (mahalle), district (ilçe), city (kent), and the region (bölge), which is referred to as “northern Kurdistan.”

The “highest” level of federation in northern Kurdistan, the DTK (Democratic Society Congress) is a mix of the rank-and-file delegated by their peers with recallable mandates, who make up 60 percent, and representatives from “more than five hundred civil society organizations, labor unions, and political parties,” who make up 40 percent, out of which approximately 6 percent is “reserved for representatives of religious minorities, academics, or others with a particular expertise.”

The proportion of the 40 percent who are similarly delegated from directly democratic, non-statist civil society groups compared to those who are unelected or elected party bureaucrats is unclear. Overlap of individuals between independent Kurdish movements and Kurdish political parties, as well as the internalization of many aspects of the directly democratic procedure by these parties, further complicates the situation. The informal consensus among witnesses, nevertheless, is that the majority of decision-making is directly democratic through one arrangement or other; that the majority of those decisions are made at the grassroots; and that the decisions are executed from the bottom-up in accordance with the federal structure.

Because the assemblies and the DTK are coordinated by the illegal KCK, of which the PKK is a part, they are designated as “terrorists” by Turkey and the so-called international community (the EU, United States and others), by association. The DTK also selects the candidates of the pro-Kurdish BDP (Peace and Democracy Party) for the Turkish Parliament, which in turn proposes “democratic autonomy” for Turkey, in some type of a combination of representative and direct democracy. In line with the federal model, it proposes the establishment of approximately 20 autonomous regions which would directly self-govern (in the anarchist and not the Swiss model) “education, health, culture, agriculture, industry, social services and security, women’s issues, youth and sports,” with the state continuing to conduct “foreign affairs, finance and defense.”

The Social Revolution Takes Off

On the ground, meanwhile, the revolution has already begun.

In Turkish Kurdistan, there is an independent educational movement of “academies” that hold discussion forums and seminars in neighborhoods. There is Culture Street, where Abdullah Demirbas, the mayor of Sur Municipality in Amed celebrates “the diversity of religions and belief systems,” declaring that “we have begun to restore a mosque, a Chaldean-Aramaic catholic church, an orthodox Armenian Church, and a Jewish Synagogue.” Elsewhere, Jongerden and Akkaya report, “DTP municipalities initiated a ‘multilingual municipality service,’ sparking heated debate. Municipality signs were erected in Kurdish and Turkish, and local shopkeepers followed suit.”

The liberation of women is pursued by the women themselves through the initiatives of the DTK’s Women’s Council, enforcing new rules like the “forty percent gender quota” in the assemblies. If a civil servant beats his wife, his salary is directly transferred to the survivor to provide for her financial security and use as she sees fit. “In Gewer, if a husband takes a second wife, half of his estate goes to his first.”

There are “Peace Villages”, new or transformed communities of co-operatives, implementing their own program fully outside of the logistical constraints of the Kurdish-Turkish war. The first such community was constructed in Hakkari province, bordering Iraq and Iran, where “several villages” joined the experiment. In Van province, an “ecological women’s village” is being built to shelter victims of domestic violence, supplying itself “with all or almost all the necessary energy.”

The KCK holds biennial meetings in the mountains with hundreds of delegates from all four countries, with the threat of the Islamic State to autonomous southern and western Kurdistan high on their agenda. The Iranian and Syrian KCK-affiliated parties, PJAK (Party for Free Life in Kurdistan) and PYD (Democratic Union Party) promote democratic confederalism as well. The Iraqi KCK party, PCDK (Party for a Democratic Solution in Kurdistan) is relatively insignificant, with the ruling centrist Kurdistan Democratic Party and its leader Massoud Barzani, president of Iraqi Kurdistan, only recently decriminalizing and starting to tolerate it.

In the northernmost mountainous areas in Iraqi Kurdistan where the majority of PKK and PJAK guerrillas live, however, radical literature and assemblies thrive, with integration between the mountains’ many Kurds continuing after decades of displacement. In recent weeks, these militants have come down from the northernmost mountains to fight alongside the Iraqi Peshmerga against ISIS, rescuing 20,000 Yazidi and Christians from the Sinjar Mountains and being visited by Barzani in a public display of gratitude and solidarity, much to the embarrassment of Turkey and the United States.

The Syrian PYD has followed Turkish Kurdistan’s lead in the revolutionary transformation of the autonomous region under its control since the outbreak of the civil war. After “waves of arrests” under Ba’athist repression, with “10,000 people [taken] into custody, among them mayors, local party leaders, deputies, cadres and activists … the Kurdish PYD forces ousted the Baath regime in northern Syria, or West Kurdistan, [and] local councils popped up everywhere.” Self-defense committees were improvised to provide “security in the wake of the collapse of the Ba’ath regime,” and “the first school teaching the Kurdish language” was established as the councils intervened in the equitable distribution of bread and gasoline.

In Turkish, Syrian and to a lesser extent Iraqi Kurdistan, women are now free to unveil and strongly encouraged to participate in social life. Old feudal ties are being broken, people are free to follow any or no religion, and ethnic and religious minorities live together peaceably. If they are able to confine the new caliphate, PYD autonomy in Syrian Kurdistan and KCK influence in Iraqi Kurdistan could ferment an even more profound explosion of revolutionary culture and values.

On June 30, 2012, the National Coordination Committee for Democratic Change (NCB), the broader revolutionary leftist coalition in Syria of which the PYD is the main group, has now embraced “the project of democratic autonomy and democratic confederalism as a possible model for Syria” as well.

Defending the Kurdish Revolution from IS

Turkey, in the meantime, has threatened to invade Kurdish territories if “terrorist bases are set up in Syria,” as hundreds of KCK (including PKK) fighters from across Kurdistan cross the border to defend Rojava (the West) from the advances of the Islamic State. The PYD alleges that Turkey’s moderate Islamist government is already engaged in a proxy war against them by facilitating the travel of international jihadists across the border to fight alongside the Islamists.

In Iraqi Kurdistan, Barzani, whose guerrillas fought alongside Turkey against the PKK in the 1990s in exchange for access to Western markets, has called for a “unified Kurdish front” in Syria through an alliance with the PYD. Barzani brokered the “Erbil Agreement” in 2012, forming the Kurdish National Council, with PYD leader Salih Muslim confirming that “all parties are serious and determined to continue working together.”

Still, while the study and practice of libertarian socialist ideas among the KCK leadership and rank-and-file is undoubtedly a positive development, it remains to be seen how serious they are about renouncing their bloody authoritarian past. The Kurdish struggle for self-determination and cultural sovereignty form a silver lining in the dark clouds gathering over the Islamic State and the bloody inter-fascist wars between Islamism, Ba’athism and religious sectarianism that gave birth to it.

A socially progressive and secular pan-Kurdish revolution with libertarian socialist elements, uniting the Iraqi and Syrian Kurds and re-invigorating the Turkish and Iranian struggles, may yet be a prospect. In the meantime, those of us who value the idea of civilization owe our gratitude to the Kurds, who are fighting the jihadists of Islamist fascism day and night on the frontlines in Syria and Iraq, defending radical democratic values with their lives.

“The Kurds have no friends but the mountains”

— Kurdish proverb