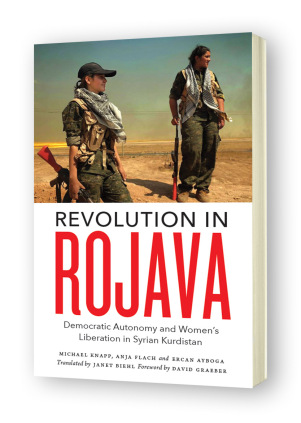

Revolution in Rojava is the first book-length account of the unique and extraordinary political situation in Rojava, Syria. In this article, Janet Biehl talks to the authors and discusses how and why the new society in Rojava so inspired them.

For decades, three million Syrian Kurds have lived under brutal repression by the Assad regime,  their identity denied, access to education and jobs refused, imprisonment and torture a way of life for those who dared object. Yet resistance has grown. By developing organisations, after the Arab Spring arrived in Syria in March 2011, the Kurds seized the moment to create a pioneering, democratic revolution. The liberation of northern Syria—Rojava—began at Kobanî on July 19th 2012, and the global history of social and political revolution would never be the same again.

their identity denied, access to education and jobs refused, imprisonment and torture a way of life for those who dared object. Yet resistance has grown. By developing organisations, after the Arab Spring arrived in Syria in March 2011, the Kurds seized the moment to create a pioneering, democratic revolution. The liberation of northern Syria—Rojava—began at Kobanî on July 19th 2012, and the global history of social and political revolution would never be the same again.

In May 2014, three Kurdish solidarity activists from Germany and Turkey decided to visit Rojava. ‘I wanted to see it, to learn from its practice’, says Michael Knapp, ‘to understand the contradictions and research the system’s difficulties. Because we can learn a lot from it for revolutionary projects in Western countries.’ With their combined language skills, contacts, and extensive knowledge of the movement, they were able to do close fieldwork and interview many people.

Upon their return, they compiled their observations into a book, Revolution in Rojava, which has just been published in English.

One of the three authors, Anja Flach, was particularly interested in studying women’s role in the revolution. Twenty years earlier, Flach had spent several years the Qandil Mountains of Northern Iraq, where she participated in the Kurdish women’s guerrilla army, the PAJK. There, she focused on political education and struggle. She observed, ‘it’s part of everyday life, in between military training, to do political analysis, to read and discuss together’. Inspired, Flach came home and immediately began to write about her experiences.

Only with the defense of Kobanî in late 2014, however, did the world finally became aware of the existence of Kurdish women fighters and commanders, equipped only with light weapons, yet successfully running IS out of the city at great risk.

But what were they actually fighting for? Little was known, says Flach, about the wide-reaching system of gender-equality that they were defending. She discovered that the implementation of these principles had been successful throughout the revolutionary society. Across the stateless democratic self-administration and throughout political organisations, leadership is dual (male-female) for every speaker position, and every committee and meeting has a forty percent gender quota. Indeed, Flach recognised these principles from her years in the Qandil Mountains. Polygamy and underage marriage have been banned, and women’s cooperatives are being constructed throughout Cizire canton, to give women economic independence, usually for the first time in their lives.

Flach found that the women in Rojava are determined to remake gender relations throughout northern Syria. She saw ‘a women’s committee in every street, and in every neighborhood a women’s council, a women’s academy, women’s security forces, and armed units’. These indefatigable activists go from house to house, informing the women at home that they have access to women’s institutions. ‘The women’s movement would like to win over and organise every woman,’ Flach says, ‘regardless of whether she is a Kurd’. Syriac women too are forming autonomous councils and military units.

For Flach, visiting Rojava was like a dream come true. ‘It was what we had been fighting for all

those years—a free society that administers itself.’ Most astoundingly, ‘in Rojava I came across many of my onetime fellow fighters again. As young women they had left Rojava to join the PKK, and now they’ve returned to defend the revolution.’

those years—a free society that administers itself.’ Most astoundingly, ‘in Rojava I came across many of my onetime fellow fighters again. As young women they had left Rojava to join the PKK, and now they’ve returned to defend the revolution.’

Ercan Ayboğa, a Kurd living in Diyarbakir, works with the Mesopotamian Ecology Movement in North Kurdistan, Southeastern Turkey, and is a key organiser against the construction of a dam at Hasankeyf, a site of major historical, ecological, and cultural importance that is poised to be flooded by the dam’s reservoir. In Rojava, with his ecologist’s eye, he was shocked by the lack of trees and biological diversity in agriculture, for example, the crops in Cizire canton were a wheat monoculture. Trained as a hydraulic engineer, he was appalled by the water crisis: ‘All the rivers were dry—even in May—or else very polluted.’

In Rojava, Ayboğa studied the communes-and-councils structure, which was set in motion by the revolution’s chief organizations: the MGRK (People’s Council of West Kurdistan), the Democratic Society Movement (TEV-DEM), and the PYD (Democratic Union Party). Shortly before the 2012 liberation, he says, they instituted a system of radical democracy that combines council and grassroots democracy. ‘On the ground are the communes, which are organised in the residential streets of cities and villages. Above them are the people’s councils in three other levels. The lower level is represented in the higher level through its coordination. At each level are nine commissions that cover the whole life like defense, women, civil society, diplomacy/politics, economy, education, and health. This system has empowered hundreds of thousands of people in a very effective way; people have started to govern themselves and to make decisions about their lives.’

As the Kurdish forces fighting IS liberate numerous villages, this system of democratic self-administration is spreading farther into northern Syria. ‘TEV-DEM activists go the villages and cities and describe themselves and what they’ve done in the past few years,’ says Ayboğa. ‘They propose that the people organise themselves in communes. We have dozens of new communes, very soon hundreds of them, with a mainly Arab population.’ He was greatly impressed by the will of the many political activists, including young people and women, hoping that their struggle be successful, overcome all challenges, and build up a new society.

The group’s third member, Michael Knapp, is a veteran of the German left since the 1990s. He describes himself not as a solidarity activist but as part of the movement for radical democracy. He took great interest in Rojava’s ‘social economy’, based on the understanding that a democratic polity requires for its existence democratic control over the economy. In contrast to neoliberalism, and to state socialism where the state administers the economy, Rojava’s social economy administers production through the democratic self-administration: the economic commissions are accountable to the communes and councils at all levels.

The revolution demands that new enterprises should be organised as structured cooperatives. ‘Cooperatives exist in all sectors of society, even the refining sector’, says Knapp. ‘Most of those the enterprises we visited were small, with some five to ten persons producing textiles, agricultural products, and groceries. But some were bigger, like a cooperative near Amûde that guarantees subsistence for more than 2,000 households’. Under the regime, Northern Syria was not industrialised, instead it is maintained as a source of raw materials and foodstuffs. However, the social economy is planning future alternative industrialisation built around ecological and communalist principles.

However, this process hasn’t yet been possible because of the war. Moreover, Rojava is under an economic embargo, imposed by hostile Turkey to the north, the Turkey-dependent KRG to the east, and the murderous IS and other Salafi-jihadist groups to the south.

Yet Rojava survives, says Flach, partly because the people have no alternative but to fight, and partly because of their organisations and their ideological background. Rojava needs international support, especially from doctors, midwives and engineers willing to go there. Financial support is also crucial, as is political support. But most importantly, says Flach, is for sympathisers to learn from the Rojava model and organise in their own countries. ‘War and industrialism, and the social and ecological disasters connected with it, are destroying the foundations of life,’ she says. ‘It is urgently necessary to organise and to construct an alternative to the capitalist patriarchy. The survival of humankind depends on it.’

————————————–

Janel Biehl is a writer, editor and translator. She was Murray Bookchin’s copyeditor for the last two decades of his professional life. Her most recent work is Ecology or Catastrophe: The Life of Murray Bookchin (2015, Oxford University Press).

Michael Knapp is a historian of radical democracy, Cofounder of the Campaign Tatort Kurdistan and member of NavDem Berlin. His research focuses on the Kurdish issue and the construction of alternatives to capitalist modernity. His research has taken him to the Middle East, where he has studied the Kurdish Liberation Struggle and the PKK.

Anja Flach is an ethnologist and member of the Rojbîn women’s council in Hamburg. She spent two years in the Kurdish women’s guerrilla army and has previously published books about her experiences.

Ercan Ayboğa is an environmental engineer and activist. Formerly living and co-founding the Tatort Kurdistan Campaign in Germany, now he lives in North Kurdistan and is politically involved in the Mesopotamian Ecology Movement, particularly in water struggles.

————————————–

Revolution in Rojava: Democratic Autonomy and Women’s Liberation in Syrian Kurdistan is available to buy from Pluto Press here.