Sarah Glynn from Scottish Solidarity with Kurdistan looks at lessons from the democratic experiment in autonomous North East Syria as a new system that could confront the ecological crisis

Our current system is destroying our planet. Capitalism depends on continuous growth, and exploits the world’s resources as though they were infinite. Capitalists are driven by individual greed; they can’t stop to consider the wider community or worry about the future, or they will lose out to their competitors. Greed and growth are the essence of capitalism, which acts as though there was no tomorrow. If capitalism continues, there won’t be.

The problem is not simply the climate change deniers, such as Trump and Bolsonaro. Those who recognise the implications of climate change, but spread illusions that the system that is creating the problem will also solve it, pose an even greater danger.

Our politicians behave as though capitalism is a fact of life that cannot be questioned, but it is a system made by human beings, and we can – in fact, must – replace it with another. Which raises the bigger question – what would that alternative system look like? What system could we create that would prioritise, not individual greed, but general well-being, that would recognise humans as social beings, and understand human society as an integral part of the wider natural world?

These questions have been asked many times, but it is only rarely that people have had the will and the opportunity to try and put answers into practical effect. Probably the most significant experiment in creating an alternative system for the common good is taking place in the autonomous, predominantly Kurdish, region of North East Syria, where a grassroots democracy is being created in line with the political philosophy of Abdullah Ocalan. People are getting the opportunity to run their local communities and address shared interests – and ecology is a central pillar. ‘Democratic Confederalism’ in North East Syria is still very much a work in progress, and it is surrounded by enemies on all sides – but it offers the world a source of hope and inspiration that we cannot afford to ignore.

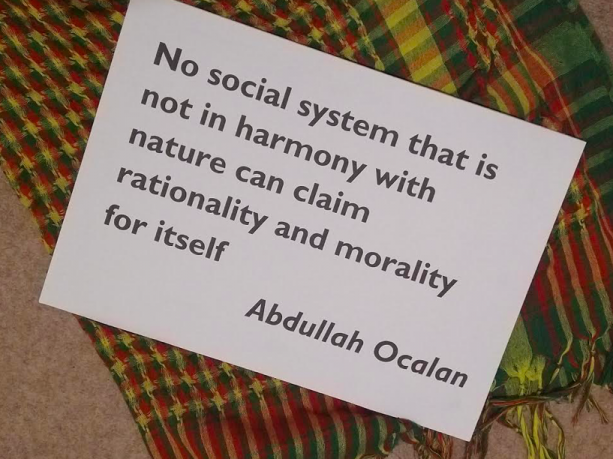

Ocalan took up the understanding of the natural world laid out in Murray Bookchin’s Ecology of Freedom. This sees human society as integral to, and emerging from, natural ecology. It rejects ideas, shared by both bible readers and modern scientists, that equate civilisation with the domination and taming of a nature from which humanity is separate and distinct. Instead, humanity needs to work with nature, and Ocalan explains that ‘No social system that is not in harmony with nature can claim rationality and morality for itself’. What he calls ‘capitalist modernity’ is not in harmony with nature, however, lessons can be learnt from earlier societies. Ocalan’s writing can be criticised for over romanticising the ancient Sumerian past and women’s affinity with the natural world, but the respect that he commands means that his words can inspire a real and vital change in outlook.

Not that we should expect miracles. Indeed, ecological achievement in North East Syria is not immediately obvious, especially with much economic activity being driven by the urgent demands of war reconstruction. Nevertheless, the radical nature of the region’s social reconstruction can form the basis for a genuinely ecological approach.

Bottom-up democracy allows local areas to focus on promoting shared communal needs and wants. Active political involvement has become an integral part of everyday life, and people are taking control of their neighbourhoods. Society rather than capital is in the driving seat. And, while small shops and businesses have been welcomed back to the bazars, the anti-capitalist stance of the dominant political ideology does not extend that welcome to big businesses and corporations, which have been actively rebuffed.

Under the Assad regime, the Kurdish areas had been regarded as Syria’s breadbasket, with most land being used for wheat. Now, a push for agricultural diversification and tree planting is coming from all levels. A more positive legacy from earlier Baathist years, when the regime adopted aspects of state socialism, is the large amount of land that is publicly owned. This has made it easier to use that land for the common good, including through co-ops run like social enterprises. So far, co-ops make up only a small fraction of the economy, but their symbolic importance as harbingers of a different way of doing things is out of proportion to their size.

This is not a fully developed system providing instant answers, and its central ecological pillar is distinctly wobbly, but North East Syria does provide a living, evolving experiment in creating a better system. We can learn from it, and we can help it resist the many external forces that would like to erase both the area’s autonomy and the dangerous ideas that have taken root there. Together, we can change the system.