AN INTERVIEW WITH ERCAN AYBOGA

As the Islamic State (IS) attacked the Kurdish city of Kobanê, the name Rojava was on every tongue. But what is this place, and who are the people live there? Ercan Ayboga visited Syrian Kurdistan in May 2014. He was interviewed in German about his trip by the online magazine Marx21. This English translation is by Janet Biehl.

Q: Briefly, what is Rojava?

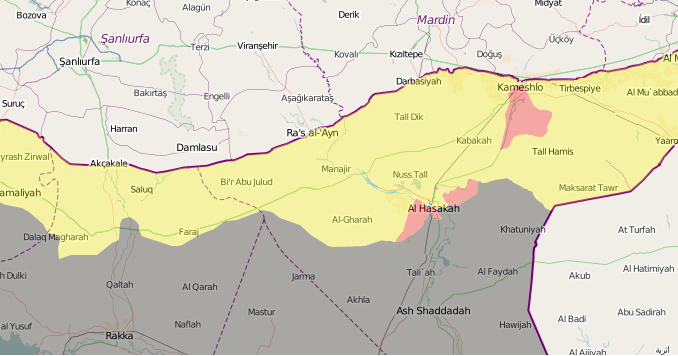

The name Rojava refers to the areas within the boundaries of the Syrian state that have a majority Kurdish population. The Kurds call this land West Kurdistan, which is what Rojava means literally. Rojava consists of the three noncontiguous areas, or cantons: Cizîrê, Kobanê, and Afrîn.

Q: Was it easy to travel there?

I traveled there with two friends from Campaign TATORT Kurdistan. We had previously been in contact with people in Rojava’s council structures (Rätestrukturen). We started out in South Kurdistan—that is, northern Iraq—in Sulaimaniya, then we passed through Mosul. We crosssed the border at Til Kocer (Rabia), but since June 2 that’s no longer possible because the IS is there now. Our journey unfolded, however, with no real problems.

Finally we reached Cizîrê in Rojava. It was easy to get there, but it’s harder to get to Afrîn and Kobanê. You have to pass through Turkey, but Turkey has sealed the borders, so nobody gets through. You’d have to do it illegally.

Q: What is daily life like there, given the Syrian civil war?

Cizîrê is the largest one of the three cantons, and we traveled to almost every city. We talked to dozens of organizations and activists. The war has not touched most of the cities of Cizîrê, except for Serê Kaniyê in 2013.

Q: What happened there?

In late 2012 and early 2013 the Al Qaeda organization Al Nusra, coming mainly from Turkey, attacked Serê Kaniyê and overran it. In one neighborhood the People’s Protection Unit (YPG) mounted a resistance. Step by step it fought back against Al Nusra and finally drove it out of the city in the summer of 2013. Now daily life goes on there on much as it did before the war. But the war in Kobanê is far more intense than was the battle for Serê Kaniyê.

Q: What about the Syrian army? Has it left Rojava in peace?

The Syrian army has contact only in three cities in Rojava. The IS and the other armed organizations are a much greater enemy. Because of the Syrian army’s weakness, it doesn’t really attack Rojava. The IS presents by far the greater threat, so no one is talking about waging a war against the Syrian state.

Most people in Cizîrê’s cities still have the same jobs as before; so do farmers on the land—it’s pretty much business as usual. Outside the war zone, production hasn’t diminished. Cars are as plentiful as before; the cities are still full of people. A few businesses have closed, especially those that depend on imports. Syrian currency is still valid in Rojava, and there’s been no great inflation, so it’s still being used.

The number of armed people in the streets has increased, although the locals no longer view them as a threat. They’re the security forces, or Asayiş, which were democratically created by the council structure.

All the symbols of the Syrian state have vanished. Now instead the symbols, images, and colors of the council structure are visible in most prominent places.

Q: What do they look like?

The colors are yellow, red, and green, mostly in stripes, whether on flags or some other surface. For public and civil institutions, their names appear in three languages: Kurdish, Arabic, and sometimes Assyrian (Aramaic). Before the revolution, Kurdish and Assyrian were forbidden. Along the streets you see many photos of local people who died in the freedom struggle. And here and there are logos of political organizations.

Q: How has life changed since the IS began attacking?

In 2014 the IS intensified its attacks on Rojava, with many strong consequences in the contested areas. Kobanê is a total war zone. In Cizîrê a few places, especially in the south between Hesekê and Til Kocer, have been affected. But Afrîn not at all, up to now. Still, almost everyone is very keyed up. Up to June 2014, the people were discussing the construction of democratic self-government much more than the war.

Q: How did Rojava originate?

In the spring of 2011, when the rebellion in Syria began, the Party of Democratic Unity (PYD)—the largest Kurdish party—in collaboration with two other Kurdish parties, began to build council structures throughout in Rojava. The PYD realized that the rebellion [against Assad’s regime] would lead to a bloody war and could reach Rojava; the Kurds, it decided, should organize themselves well in advance. So in the summer of 2011 the People’s Council of West Kurdistan (MGRK) came into existence, and it soon gained the support of the majority of the people.

On July 19, 2012, a new phase began when a mostly nonviolent popular revolt liberated the city of Kobanê. That revolt spread to all of Rojava within a few weeks. The thinned-out forces of the state were soon surrounded, and Rojava allowed them safe conduct to the other regions of Syria.

Thereafter the council structures democratically took over Rojava’s government, and since then, with their commissions and enterprises, the councils have organized Rojava’s economic, social, and political life. Except, that is, in the city of Qamişlo, one quarter of which is controlled by the state regime. The YPG protected the cantons, ensuring that they were spared the catastrophic war in Syria. At first it deflected attacks from the FSA and Al Nusra, but since the end of 2013 it has been mainly fighting the IS.

Q: How big is Rojava?

It isn’t one continuous area. The three cantons are divided by strips of land that are majority Arab. Cizîrê is more than twice as large as the other two cantons. More than 600,000 people live in Afrîn, many of them refugees. Kobanê, at mid-September, had more than 300,000, and Cizîrê has more than 1.4 million people. The largest city is Qamişlo, with more than 400,000 people—it’s the center of Rojava.

The people in Cizîrê are ethnically and religiously diverse. Many Arabs and Christian Assyrians live there, as do Armenians—for decades they have lived peacefully with the Kurds.

Q: What is the economy based on?

Agriculture is dominant in all three cantons. Kobanê grows both wheat and olives. Cizîrê specializes in wheat, and Afrîn, olives. That specialization is a disadvantage now because the three regions are so isolated. In foodstuffs, we have a surplus of bread, bulgur, lentils, olive products, and milk products. There aren’t many kinds of vegetables, or much fruit. But the council structure has ensured solidarity so that no one goes hungry.

One advantage in Cizîrê is that it has petroleum. Thanks to a refinery that’s been improvised, diesel is plentiful, and it’s sold more cheaply than in Baath times. It’s used regionally and locally to run generators, providing power both for households and for production.

Again, the council structures have prevented economic collapse, imposing price controls and considerably reducing the black market.

Q: Describe these council structures. How do they function?

They’re everywhere—they’re are the dominant element in Rojava’s common life. Now that the Syrian state is no longer present, the councils decide and coordinate everything. If they didn’t, it would all would fall into chaos. But they should not be considered some kind of emergency management.

The councils start, at the lowest level, at the communes, which consist of 30 to 150 households, both in cities and in rural villages. The next level up is the neighborhood councils in the cities, paralleled in the countryside by the village community councils. At the third level we have the area councils, the jurisdictions of which are a city with its surrounding land. The area councils then constitute the highest council–the People’s Council of West Kurdistan (MGRK).

Q: What’s the relationship between the different levels—the neighborhood councils, the area councils, and the People’s Council?

Each commune is coordinated by two chairs—a woman and a man—and by representatives of their various commissions. The chairs are elected for terms of one or two years. Every commune—and indeed each level of the council structure–has the following commissions: women, economy, politics, defense, civil society/occupations, and education.

The two coordinating chairs represent the commune at the next level, the neighborhood. This second level—consisting of 7 to 30 communes—choose from their members a two-person chair and also form the same commissions. Their chairs represent the neighborhood council in the area council. The area councils too have two chairs and form commissions, and their chairs go tot the highest level, the MGRK. The area councils and the MGRK are coordinated by the Tev-Dem (Movement for a Democratic Society), which also includes NGOs and all political parties that support the council system, represented by five people.

Q: What democratic controls are in place? Is there an imperative mandate?

Yes, there’s an imperative mandate. Elections take place every one or two years—the structures of a given locality decide when. The coordinating chairs meet weekly, and their meetings are open to everyone from their jurisdictions.

Q: You spoke of commissions. Why are they necessary?

The six commissions are very important—they handle most of the work. Through them tens of thousands of people actively organize their lives. The PYD’s decision to build the MGRK and to renounce strong party structures has proved to be very astute.

Probably the most important commissions are the women’s commissions or councils, which exist at every level. They cooperate together on the basic liberation of women.

Now that the MGRK have operated for three years, all three Kurdish parties support it, as do the Assyrians and some of the Arabs. Unfortunately there’s also a conservative-neoliberal party bloc, made up of eight parties. The bloc is called the ENKS, and it opposes the MGRK. It even refused to participate when fifty Kurdish, Arab, and Assyrian parties and organizations came together to accept a common social contract and form a transitional government.

Q: Whose interests does the conservative-neoliberal bloc represent? What’s its base?

It’s based mainly in a few clans and on the upper and middle stratum, which in Rojava is relatively not very distinct. And a few people from the lower classes are also close to this bloc. The ENKS is financed and directed by the regional government of South Kurdistan. It has joined the Syrian National Coalition, the larger opposition alliance that includes the Muslim Brotherhood (Muslimbrüder) and the Free Syrian Army (FSA), even though the those groups don’t recognized the basic rights of Kurds and are very dependent on Turkey, the Gulf States, and the West. The ENKS advocates a federal structure like that of South Kurdistan, and it want to achieve it through Western intervention. But before 2014 the ENKS was losing a lot of ground in Rojava, and it doesn’t play much of a role.

Q: Why is there a transitional government at all, alongside the council structures? What’s its purpose?

Most Kurds support the MGRK, but most non-Kurds don’t. The purpose of the transitional government is to include as many groups and people as possible. And it’s an effort to achieve legitimacy in Syria, in the Middle East, and in the world. Unfortunately, a council structure wouldn’t be respected internationally.

The transitional government emerged from the council structures and doesn’t contradict them—it recognizes their legitimacy. It’s much more dependent on them than vice versa, since after three years they are functioning so well. The council structures coordinate the economy; there aren’t any large private enterprises.

Q: Is there an additional level of councils in enterprises? How do they fit in with the rest of the council structure?

The private firms have is no council stricture, since only about fifteen people at most work in them. The public enterprises are more important, because they employ more people. Labor unions have recently been brought in, coordinated by the council structures. We are in a transitional phase, it’s all to be configured along direct-democratic lines.

Q: Has private ownership of the means of production been wholly abolished? Or are there still owners and workers in smaller enterprises and businesses?

Private ownership hasn’t been abolished. Personal property has not been touched. The MGRK structures are very conscious about class relations, but at present no one is talking about socializing all the means of production. Because private ownership doesn’t play a great role in the economy. The current politics just aren’t conducive to an increase in privately owned means of production.

Up to 20 percent of the land belongs to large landholders, but land confiscated from the Syrian state has been distributed free to the poorest people in Rojavan society.

In short: the council structures—and also the transitional government, albeit in somewhat weaker form—are guided by the paradigm of a democratic, gender-equal, and ecological society. They reject bourgeois parliamentarism, one-party rule, the subordination of women, conservative structures, and the destructive logic of capitalism and its logic of exploitation.

Q: What social and political conflicts exist there in Rojava?

There’s a visible contradiction as to whether the council structure and the transitional government can continue to coexist. Over the long term that will have to be resolved.

Even given the strong solidarity and mutual aid, employment is an issue, and it’s not small. Many young people are leaving the land. The general political uncertainty is contributing to the problem.

The existing large landownership stands in contradiction to the cooperatives that are being created both in the city and in the countryside. The profitability of the enterprises created by the council structures will eventually have to be ensured.

The many refugees in Rojava are somewhat burdening the economy. But people in the society must have better housing, jobs, and social contacts. Including them in a good way should be the goal.

The embargo imposed by Turkey must be lifted, since as long as it’s in place, Rojava cannot export either petroleum or wheat. Being able to do so would strengthen the economy enormously, and would allow scarce goods to be introduced.

The insufficient electrical power considerably limits both life and the economy. There’s a lot of complaining about it.

Medications to treat chronic disease aren’t available, so chronically ill people have to leave the land, if they can, or else buy the necessary medications on the black market at a very high price.

The cooperatives that have been built have to advance further, because they offer alternative possibilities of employment to women, who have been strongly oppressed and are now politically engaged.

Q: In June 2013 many cities on Rojava saw protests against the PYD’s security forces. People were protesting the forces’ harsh methods and the arrest of political activists. What is the relationship of the PYD to the other leftist parties and organizations?

Yes, in many cities there were protests against the Asayis, the council structures’ security forces. The Asayis is not answerable to the PYD, by the way, although this party is very important. The protests were mostly organized by the ENKS. It’s true that in the beginning the Asayis in several cases were very harsh, but this was not the general rule.

And yes, it also committed some human rights abuses—in one case several people died. We investigated it. The Asayis have in the meantime learned a lot and are working to improve. All Asayis attend a seminar every week to learn about more humane ways of dealing with people.

Actually most people in Rojava today are very positive about the Asayis. They come from among their own—they aren’t outsiders brought in from some other place. In 2014 there were almost no protests against the Asayis, which shows that the situation has improved.

Q: And what is the connection to South Kurdistan and its ruling KDP?

Starting in early 2013, Rojava’s relations with South Kurdistan (the KRG) were poor, mainly because of South Kurdistan. In April 2014 the KRG built a trench and a wall against Rojava, to obstruct trade and to enforce the embargo against Rojava. It even denied that there’s been a revolution here at all. Finally at the end of October 2014, as a result of the struggle for Kobanê, all parties of Rojava—including the KRG, led by the KDP, and the PKK—came to an agreement. The two sides are drawing closer. Kobanê and all Rojava benefit from that development. But we know that the KDP would like very much to gain more power in Rojava and strip the revolution of its emancipatory content. The council structures, however, are confident of the people’s support and don’t believe their revolution can be either defeated or stolen.

Q: What would the German government do if it really wanted to help people in Kobanê?

It would to exert pressure on Turkey to open a permanent corridor to Kobanê. The corridor is important because YPG units from the two other regions of Rojava need it to get to Kobanê.

It would persuade Turkey to finally stop supporting IS—Turkish support for the IS is at present unabated.

And finally, it would have to lift the ban on the PKK, a ban that intimidates thousands of Kurds and obstructs their solidarity with Kobanê.

Ercan Ayboga lives in Germany and writes regularly for Kurdistan Report and Yeni Özgür Politika. He is active in Campaign TATORT Kurdistan. At the moment he and the two other delegation participants are writing a book [now published] about the revolution in Rojava.

This interview was originally published in Marx21 on November 10, 2014. http://marx21.de/kurdisches-leben-rojava/ It has been translated from the German by Janet Biehl.