In the ongoing discussions of the social experiment taking place in Rojava, the economic aspect often tends to get neglected. You can read a lot about the military aspect, the war against ISIS, co-operation with US forces and so on, and a lot about the political ideologies, the new decision-making structures that have been set up and all the rest of it; but the questions of everyday life, what people have to do to get food to eat and houses to live in, and how this compares to what it was like before, or how it differs from the rest of the world, tend to attract less attention.

As a partial corrective to that, I’d recommend reading this short report from the Washington Institute. The source is a US-based institute that aims to “advance a balanced and realistic understanding of American interests in the Middle East and to promote the policies that secure them”, so the author’s clearly not likely to be very sympathetic to any kind of radical social change; but in the absence of informed discussion about Rojava’s economics from more revolutionary perspectives, it’s a start.

From the report:

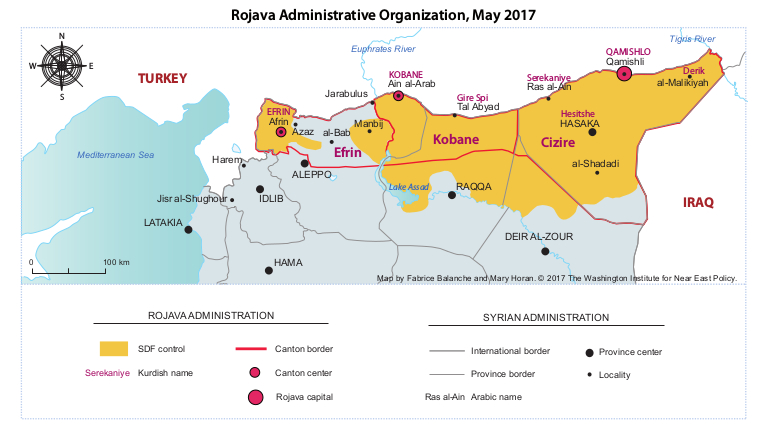

“The three cantons are supposed to be governed by an elected assembly that controls Rojava’s executive bureau, but elections have not yet taken place. TEV-DEM scheduled them for an unspecified day in 2017, contrary to Bookchin’s model of creating municipalities that elect delegates to confederal councils. In Rojava, such municipalities are known as communes (“komun” in Kurdish), each containing roughly 150 houses and around a thousand inhabitants. An elected communal council manages relations between individual villages and the established authorities who still run local public services such as water and electricity, since the administrative framework of the prewar municipalities has not disappeared. Ideally, new municipalities would arise naturally from the communes, but in reality the new and old structures exist in parallel. The communes deliver certificates to the population for bread and fuel at low prices; they also supervise the local community and participate in its political education. This corresponds roughly with the village “committees” of Communist China.

In addition, Rojava’s communes are supposed to organize economic life by promoting cooperatives. In the countryside, farmers are organized in groups of fifteen and asked to work together and exchange surplus production with other cooperatives, including in the cities. This practice is in line with the goal of designing communes to be self-sufficient, with the eventual aim of eliminating traders and money while establishing a bartering system.

Yet skepticism is warranted about the principles behind these measures and their application on the ground. Until recently, the war’s economic disruption pushed Rojava’s population to organize a subsistence economy, and the Kurdish zone’s isolation created practical reasons to favor self-sufficiency. Yet now that overland links are reopening, this policy can only be justified on the ideological level.

INCOMPATIBLE WITH ECONOMIC DIVERSIFICATION

In the agricultural sector, the new authorities in Jazira want to reduce the canton’s share of cereals and cotton, the main crops produced in the area, in order to make room for activities that would make local communities more self-sufficient in feeding themselves, such as market gardening and arboriculture. To effect this change, large estates and public lands need to be entrusted to the population and organized in cooperatives. Yet the people seem unlikely to embrace this new economic system. The TEV-DEM program could seduce the landless peasants of Jazira, to whom the PYD plans to distribute former public domains, but it is unpalatable to existing owner-farmers, who would no doubt prefer to continue working individually. Moreover, market gardening requires much greater personal investment than cereal farming, which is hardly compatible with the collectivist spirit the PYD has sought to inculcate.

Meanwhile, industry is almost absent from all of the cantons, mainly because the Assad regime preferred to keep things that way for “security reasons.” For instance, only two cotton mills were built in the Hasaka area of Jazira. This means Rojava authorities will not have to nationalize any factories — but only because such facilities are nonexistent. To fill this gap and meet local needs, they would like to develop agro-food and manufacturing industries. They might also try to make fuller use of local oil resources (estimated at 150,000 barrels per day in 2011), which would require foreign investment.

Yet attracting investors into such an anti-capitalist system would be difficult. Entrepreneurship is encouraged in Rojava, but only within the framework of cooperatives. Similarly, engineers and technicians are needed to work for the “revolution,” but individuals who have the necessary degrees and training tend to leave Rojava because salaries are too low there. Moreover, many young men fear conscription and prefer to take refuge in Iraq. The middle classes in particular are experiencing this demographic hemorrhage, since liberal professionals and entrepreneurs are largely excluded from the economic system currently being set up.

REVEALING ROJAVA’S RELATIONS WITH DAMASCUS

The application of Ocalan’s theories is still modest in Rojava’s economic sphere, as the PYD is aware that it risks alienating a large part of the population, especially those who only rallied to the group for fear of the Islamic State. The reopening of land communications with the Assad regime zone in western Syria is encouraging a return to the lucrative exportation of cereals and cotton. Moreover, manufactured goods from the regime zone will likely flood Rojava markets before any local production could develop. Accordingly, local authorities may resort to protectionism to defend the cantons economically, perhaps by imposing tariffs and cutting off the western Syrian market.

If the PYD’s cooperative economic system fails due to these pressures, the party would have two choices: coercing locals into accepting Ocalan’s theories, or declaring a “pause” in implementation due to wartime circumstances, much like Vladimir Lenin did with the Soviet Union’s New Economic Policy in 1920. In the first case, the “communalization” of Rojava’s economy would entail the expropriation of property belonging to certain social groups, namely, constituencies that are deemed opponents of the PYD. This property would then be redistributed to the party’s own base with the objective of strengthening its influence and eliminating the Assad regime’s. Such efforts would also indicate a separatist mindset, despite the federal model the PYD has been outwardly promoting.

In the second case, a “pause” in economic collectivization would likely spur the PYD to renounce its intention of changing Rojava society and agree to normalize relations with Damascus. The Kurdish cantons would then be reinstated in the Syrian economic space and the impediments to private initiative lifted. Whichever approach the party chooses, the local population — Kurdish and non-Kurdish — will be more inclined to accept the pursuit of some form of autonomy if their living conditions improve.”